Unless you’ve been living in a news vacuum for the past few weeks, you can’t have missed the catastrophic news from Japan about earthquakes, tsunamis, and nuclear meltdowns. I’m not sure anyone could come up with a worse triad of disasters capable of instilling helplessness and fear in the human soul.

Without offering these numbers as precise values, it’s impossible for me to comprehend how so much earth can move so violently for over two minutes, create an undersea trench over 180 miles long, displace millions of tons of water with enough force to send a wave 30 feet high ashore to wipe the ground clean for up to 6 miles inland, move Japan 18 feet closer to North America, alter the earth’s movement around its own axis and change the measurement of time.

And then well before the shock of these events can even begin to abate, we are bombarded with news reports about the critical state of the Japanese nuclear power industry and the possibility of even more disasterous consequences in the aftermath of nature’s wrath. The problem with these dramatic predictions, however, is that most people who hear them can’t evaluate their scientific validity.

And then well before the shock of these events can even begin to abate, we are bombarded with news reports about the critical state of the Japanese nuclear power industry and the possibility of even more disasterous consequences in the aftermath of nature’s wrath. The problem with these dramatic predictions, however, is that most people who hear them can’t evaluate their scientific validity.

I read a letter to the editor in the Austin American-Statesman just this morning from a reader who scoffs (with profanity, according to him) about the reports urging calm because the situation is not as dire as it may appear.

I read a letter to the editor in the Austin American-Statesman just this morning from a reader who scoffs (with profanity, according to him) about the reports urging calm because the situation is not as dire as it may appear.

I don’t know whom to believe, but I can decide who gets the majority of my credibility votes. And in the case of nuclear power, it won’t be just anyone.

A friend sent me what follows, and from this chair, the explanation has all the trappings of being reliable. I urge you to read it to the end and make up your own mind. It comes to us through a series of sources, which I have reproduced here exactly as I received them.

<http://theenergycollective.com/all/12315> Posted March 15, 2011 by Barry Brook <http://theenergycollective.com/user/48910>

Editors’ Note: this post was written by a person who knew of nuclear physics but was not a nuclear engineer nor physicist, but an economist. This content has now been edited for accuracy by the MIT scientific community. Below is an updated version of the original post written by Josef Oehmen <http://mitnse.com/2011/03/13/why-i-am-not-worried-about-japans-nuclear-reactors/>

This post originally appeared on Morgsatlarge. Members of the NSE community have edited the original post and will be monitoring and posting comments, updates, and new information. Please visit to learn more. Note that the title of the original blog does not reflect the views of the authors of the site. The authors have been monitoring the situation, and are presenting facts on the situation as they develop. The original article was adopted as the authors believed it provided a good starting point to provide a summary background on the events at the Fukushima plant.

We will have to cover some fundamentals, before we get into what is going on.

Construction of the Fukushima nuclear power plants

The plants at Fukushima are Boiling Water Reactors (BWR for short). A BWR produces electricity by boiling water, and spinning a a turbine with that steam. The nuclear fuel heats water, the water boils and creates steam, the steam then drives turbines that create the electricity, and the steam is then cooled and condensed back to water, and the water returns to be heated by the nuclear fuel. The reactor operates at about 285 °C.

The nuclear fuel is uranium oxide. Uranium oxide is a ceramic with a very high melting point of about 2800 °C. The fuel is manufactured in pellets (cylinders that are about 1 cm tall and 1 com in diameter). These pellets are then put into a long tube made of Zircaloy (an alloy of zirconium) with a failure temperature of 1200 °C (caused by the auto-catalytic oxidation of water), and sealed tight. This tube is called a fuel rod. These fuel rods are then put together to form assemblies, of which several hundred make up the reactor core.

The solid fuel pellet (a ceramic oxide matrix) is the first barrier that retains many of the radioactive fission products produced by the fission process. The Zircaloy casing is the second barrier to release that separates the radioactive fuel from the rest of the reactor.

The core is then placed in the pressure vessel. The pressure vessel is a thick steel vessel that operates at a pressure of about 7 MPa (~1000 psi), and is designed to withstand the high pressures that may occur during an accident. The pressure vessel is the third barrier to radioactive material release.

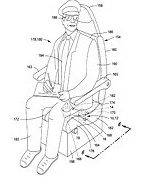

The entire primary loop of the nuclear reactor – the pressure vessel, pipes, and pumps that contain the coolant (water) – are housed in the containment structure. This structure is the fourth barrier to radioactive material release. The containment structure is a hermetically (air tight) sealed, very thick structure made of steel and concrete. This structure is designed, built and tested for one single purpose: To contain, indefinitely, a complete core meltdown. To aid in this purpose, a large, thick concrete structure is poured around the containment structure and is referred to as the secondary containment.

Both the main containment structure and the secondary containment structure are housed in the reactor building. The reactor building is an outer shell that is supposed to keep the weather out, but nothing in. (this is the part that was damaged in the explosions, but more to that later).

Fundamentals of nuclear reactions

The uranium fuel generates heat by neutron-induced nuclear fission. Uranium atoms are split into lighter atoms (aka fission products). This process generates heat and more neutrons (one of the particles that forms an atom). When one of these neutrons hits another uranium atom, that atom can split, generating more neutrons and so on. That is called the nuclear chain reaction. During normal, full-power operation, the neutron population in a core is stable (remains the same) and the reactor is in a critical state.

It is worth mentioning at this point that the nuclear fuel in a reactor can never cause a nuclear explosion like a nuclear bomb. At Chernobyl, the explosion was caused by excessive pressure buildup, hydrogen explosion and rupture of all structures, propelling molten core material into the environment. Note that Chernobyl did not have a containment structure as a barrier to the environment. Why that did not and will not happen in Japan, is discussed further below.

In order to control the nuclear chain reaction, the reactor operators use control rods. The control rods are made of boron which absorbs neutrons. During normal operation in a BWR, the control rods are used to maintain the chain reaction at a critical state. The control rods are also used to shut the reactor down from 100% power to about 7% power (residual or decay heat).

The residual heat is caused from the radioactive decay of fission products. Radioactive decay is the process by which the fission products stabilize themselves by emitting energy in the form of small particles (alpha, beta, gamma, neutron, etc.). There is a multitude of fission products that are produced in a reactor, including cesium and iodine. This residual heat decreases over time after the reactor is shutdown, and must be removed by cooling systems to prevent the fuel rod from overheating and failing as a barrier to radioactive release. Maintaining enough cooling to remove the decay heat in the reactor is the main challenge in the affected reactors in Japan right now.

It is important to note that many of these fission products decay (produce heat) extremely quickly, and become harmless by the time you spell “R-A-D-I-O-N-U-C-L-I-D-E.” Others decay more slowly, like some cesium, iodine, strontium, and argon.

What happened at Fukushima (as of March 12, 2011)

The following is a summary of the main facts. The earthquake that hit Japan was several times more powerful than the worst earthquake the nuclear power plant was built for (the Richter scale works logarithmically; for example the difference between an 8.2 and the 8.9 that happened is 5 times, not 0.7).

When the earthquake hit, the nuclear reactors all automatically shutdown. Within seconds after the earthquake started, the control rods had been inserted into the core and the nuclear chain reaction stopped. At this point, the cooling system has to carry away the residual heat, about 7% of the full power heat load under normal operating conditions.

The earthquake destroyed the external power supply of the nuclear reactor. This is a challenging accident for a nuclear power plant, and is referred to as a “loss of offsite power.” The reactor and its backup systems are designed to handle this type of accident by including backup power systems to keep the coolant pumps working. Furthermore, since the power plant had been shut down, it cannot produce any electricity by itself.

For the first hour, the first set of multiple emergency diesel power generators started and provided the electricity that was needed. However, when the tsunami arrived (a very rare and larger than anticipated tsunami) it flooded the diesel generators, causing them to fail.

One of the fundamental tenets of nuclear power plant design is “Defense in Depth.” This approach leads engineers to design a plant that can withstand severe catastrophes, even when several systems fail. A large tsunami that disables all the diesel generators at once is such a scenario, but the tsunami of March 11th was beyond all expectations. To mitigate such an event, engineers designed an extra line of defense by putting everything into the containment structure (see above), that is designed to contain everything inside the structure.

When the diesel generators failed after the tsunami, the reactor operators switched to emergency battery power. The batteries were designed as one of the backup systems to provide power for cooling the core for 8 hours. And they did.

After 8 hours, the batteries ran out, and the residual heat could not be carried away any more. At this point the plant operators begin to follow emergency procedures that are in place for a “loss of cooling event.” These are procedural steps following the “Depth in Defense” approach. All of this, however shocking it seems to us, is part of the day-to-day training you go through as an operator.

At this time people started talking about the possibility of core meltdown, because if cooling cannot be restored, the core will eventually melt (after several days), and will likely be contained in the containment. Note that the term “meltdown” has a vague definition. “Fuel failure” is a better term to describe the failure of the fuel rod barrier (Zircaloy). This will occur before the fuel melts, and results from mechanical, chemical, or thermal failures (too much pressure, too much oxidation, or too hot).

However, melting was a long ways from happening and at this time, the primary goal was to manage the core while it was heating up, while ensuring that the fuel cladding remain intact and operational for as long as possible.

Because cooling the core is a priority, the reactor has a number of independent and diverse cooling systems (the reactor water cleanup system, the decay heat removal, the reactor core isolating cooling, the standby liquid cooling system, and others that make up the emergency core cooling system). Which one(s) failed when or did not fail is not clear at this point in time.

Since the operators lost most of their cooling capabilities due to the loss of power, they had to use whatever cooling system capacity they had to get rid of as much heat as possible. But as long as the heat production exceeds the heat removal capacity, the pressure starts increasing as more water boils into steam. The priority now is to maintain the integrity of the fuel rods by keeping the temperature below 1200°C, as well as keeping the pressure at a manageable level. In order to maintain the pressure of the system at a manageable level, steam (and other gases present in the reactor) have to be released from time to time. This process is important during an accident so the pressure does not exceed what the components can handle, so the reactor pressure vessel and the containment structure are designed with several pressure relief valves. So to protect the integrity of the vessel and containment, the operators started venting steam from time to time to control the pressure.

As mentioned previously, steam and other gases are vented. Some of these gases are radioactive fission products, but they exist in small quantities. Therefore, when the operators started venting the system, some radioactive gases were released to the environment in a controlled manner (ie in small quantities through filters and scrubbers). While some of these gases are radioactive, they did not pose a significant risk to public safety to even the workers on site. This procedure is justified as its consequences are very low, especially when compared to the potential consequences of not venting and risking the containment structures’ integrity.

During this time, mobile generators were transported to the site and some power was restored. However, more water was boiling off and being vented than was being added to the reactor, thus decreasing the cooling ability of the remaining cooling systems. At some stage during this venting process, the water level may have dropped below the top of the fuel rods. Regardless, the temperature of some of the fuel rod cladding exceeded 1200 °C, initiating a reaction between the Zircaloy and water. This oxidizing reaction produces hydrogen gas, which mixes with the gas-steam mixture being vented. This is a known and anticipated process, but the amount of hydrogen gas produced was unknown because the operators didn’t know the exact temperature of the fuel rods or the water level.

Since hydrogen gas is extremely combustible, when enough hydrogen gas is mixed with air, it reacts with oxygen. If there is enough hydrogen gas, it will react rapidly, producing an explosion. At some point during the venting process enough hydrogen gas built up inside the containment (there is no air in the containment), so when it was vented to the air an explosion occurred. The explosion took place outside of the containment, but inside and around the reactor building (which has no safety function). Note that a subsequent and similar explosion occurred at the Unit 3 reactor. This explosion destroyed the top and some of the sides of the reactor building, but did not damage the containment structure or the pressure vessel. While this was not an anticipated event, it happened outside the containment and did not pose a risk to the plant’s safety structures.

Since some of the fuel rod cladding exceeded 1200 °C, some fuel damage occurred. The nuclear material itself was still intact, but the surrounding Zircaloy shell had started failing. At this time, some of the radioactive fission products (cesium, iodine, etc.) started to mix with the water and steam. It was reported that a small amount of cesium and iodine was measured in the steam that was released into the atmosphere.

Since the reactor’s cooling capability was limited, and the water inventory in the reactor was decreasing, engineers decided to inject sea water (mixed with boric acid – a neutron absorber) to ensure the rods remain covered with water. Although the reactor had been shut down, boric acid is added as a conservative measure to ensure the reactor stays shut down. Boric acid is also capable of trapping some of the remaining iodine in the water so that it cannot escape, however this trapping is not the primary function of the boric acid.

The water used in the cooling system is purified, demineralized water. The reason to use pure water is to limit the corrosion potential of the coolant water during normal operation. Injecting seawater will require more cleanup after the event, but provided cooling at the time.

This process decreased the temperature of the fuel rods to a non-damaging level. Because the reactor had been shut down a long time ago, the decay heat had decreased to a significantly lower level, so the pressure in the plant stabilized, and venting was no longer required.

Units 1 and 3 are currently in a stable condition according to TEPCO press releases, but the extent of the fuel damage is unknown. That said, radiation levels at the Fukushima plant have fallen to 231 micro sieverts (23.1 millirem) as of 2:30 pm March 14th (local time).

In a previous post titled “JSF Circus Act – The Clowns Take the Stage,” I addressed recent disturbing developments in the already troubled Joint Strike Fighter program in which the Marine F-35B V/STOL (vertical/short takeoff & landing) variant has come under fire and faces an uncertain future.

In a previous post titled “JSF Circus Act – The Clowns Take the Stage,” I addressed recent disturbing developments in the already troubled Joint Strike Fighter program in which the Marine F-35B V/STOL (vertical/short takeoff & landing) variant has come under fire and faces an uncertain future. On January 6, SecDef Robert Gates announced that while the Navy and Air Force JSF versions are proceeding satisfactorily, he was putting the Marine Corps’ F-35B JSF on a two-year probation because of “significant testing problems which may lead to a redesign of the aircraft’s structure and propulsion, changes that could add yet more weight and more cost to an aircraft that has little capacity to absorb more of either.” In the Pentagon’s fiscal year 2012 budget request, Gates keyed on the technical and schedule hiccups with the Lockheed Martin airframe and Pratt & Whitney primary engine.

On January 6, SecDef Robert Gates announced that while the Navy and Air Force JSF versions are proceeding satisfactorily, he was putting the Marine Corps’ F-35B JSF on a two-year probation because of “significant testing problems which may lead to a redesign of the aircraft’s structure and propulsion, changes that could add yet more weight and more cost to an aircraft that has little capacity to absorb more of either.” In the Pentagon’s fiscal year 2012 budget request, Gates keyed on the technical and schedule hiccups with the Lockheed Martin airframe and Pratt & Whitney primary engine. To support that opinion, Amos pointed out that since January, the F-35B has carried out 140 percent of its scheduled flights, achieved 200 percent of its scheduled test points, and is conducting four to five times as many vertical landings as it did last year. He told lawmakers recently that he is closely monitoring development of his service’s variant and stressed that he believes the B model is “vital” to his service’s ability to conduct expeditionary operations. “During the next two years of F-35B scrutiny, I will be personally involved with the program and closely supervising it. Continued support and funding from Congress is of utmost importance.”

To support that opinion, Amos pointed out that since January, the F-35B has carried out 140 percent of its scheduled flights, achieved 200 percent of its scheduled test points, and is conducting four to five times as many vertical landings as it did last year. He told lawmakers recently that he is closely monitoring development of his service’s variant and stressed that he believes the B model is “vital” to his service’s ability to conduct expeditionary operations. “During the next two years of F-35B scrutiny, I will be personally involved with the program and closely supervising it. Continued support and funding from Congress is of utmost importance.” Amos said the F-35B’s structural issues, bulkheads and weight gain, “are progressing well. I’m going to pay attention to the aircraft performance, how it’s doing in flight both in vertical and horizontal flight, the weight growth of the airplane, which in a vertical-landing airplane is very critical. Right now, we are on a good glide slope in weight growth, and they’re not going to add a pound that I’m not aware of to that airplane. We have to talk about it.” Amos added that engineering challenges and test performance are “on his radar.” Note again the aviator-tinged buzz words.

Amos said the F-35B’s structural issues, bulkheads and weight gain, “are progressing well. I’m going to pay attention to the aircraft performance, how it’s doing in flight both in vertical and horizontal flight, the weight growth of the airplane, which in a vertical-landing airplane is very critical. Right now, we are on a good glide slope in weight growth, and they’re not going to add a pound that I’m not aware of to that airplane. We have to talk about it.” Amos added that engineering challenges and test performance are “on his radar.” Note again the aviator-tinged buzz words. Amos emphasized he believes the F-35B is vital for use on large-deck amphibious ships. “This is more than just the Marine Corps,” the general told Sen. Kay Hagan (D-N.C.). “If we lose the F-35B, there is no plan B for fixed-wing airplanes on the large-deck amphibs. Our nation’s capability to project power and influence in critical situations will be cut. So the F-35B is a requirement. I’m optimistic. What I’m seeing now is very encouraging.”

Amos emphasized he believes the F-35B is vital for use on large-deck amphibious ships. “This is more than just the Marine Corps,” the general told Sen. Kay Hagan (D-N.C.). “If we lose the F-35B, there is no plan B for fixed-wing airplanes on the large-deck amphibs. Our nation’s capability to project power and influence in critical situations will be cut. So the F-35B is a requirement. I’m optimistic. What I’m seeing now is very encouraging.”