My original intent for the Visitor Stories logbook, to serve as a destination for personal flying experiences of aviators and “normal” folks as well, has never come to fruition by receiving much interest. Three notable exceptions came from fellow writers who graciously responded to my pleas for content and contributed interesting anecdotes: one humorous, one frightening experience told with a bit of after-the-fact humor, and one poignant story of a young-boy-turned-man’s fascination with airplanes and being touched by the tragic death of a close friend’s sister in the crash of an airliner.

Unwilling to abandon the idea of incorporating “guest bloggers,” I decided to alter the concept by including articles from other sources. In the seven months since launching this blog, I’ve published in the Visitor Stories logbook my personal tribute to a WWII fighter pilot, a seven-part account of the Doolittle raid on Tokyo during WWII by a participant, and the harrowing story of an airshow pilot who literally pulled the wings off an F-100 Super Sabre and survived by a matter of seconds and a few extra feet of altitude.

A good friend and fellow aviator recently sent me the following account of an incident that ultimately altered the course of the war in the Pacific and saved the lives of countless American fighter pilots. Initially tempted to publish this in the Single Ship logbook, I changed my mind because this is someone else’s account of an historical event. And although the author didn’t visit this site except through the actions of someone else, and he doesn’t have a clue about who I am and couldn’t care less, I’m guessing that he’d have no quarrel with my sharing this story. For anyone, aviator or not, interested in the history of a time in the world when all things good were threatened with extinction by the rapidly expanding obscenity of the Axis Powers, this is a remarkable tale extremely well told.

Jim Rearden, a forty-seven-year resident of Alaska, is the author of fourteen books and more than five hundred magazine articles, mostly about Alaska. Among his books is Koga’s Zero: The Fighter That Changed World War II, which can be purchased from Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, 713 South Third Street West, Missoula, MT 59801.

Note: For an excellent source of additional information on the Mitsubishi A6M Zero-Sen fighter, see Larry Dwyer’s The Aviation History On-Line Museum.

Koga’s Zero

by Jim Rearden

In April 1942 thirty-six Zeros attacking a British naval base at Colombo, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), were met by about sixty Royal Air Force aircraft of mixed types, many of them obsolete. Twenty-seven of the RAF planes went down: fifteen Hawker Hurricanes (of Battle of Britain fame), eight Fairey Swordfish, and four Fairey Fulmars. The Japanese lost one Zero.

In April 1942 thirty-six Zeros attacking a British naval base at Colombo, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), were met by about sixty Royal Air Force aircraft of mixed types, many of them obsolete. Twenty-seven of the RAF planes went down: fifteen Hawker Hurricanes (of Battle of Britain fame), eight Fairey Swordfish, and four Fairey Fulmars. The Japanese lost one Zero.

Five months after America’s entry into the war, the Zero was still a mystery to U.S. Navy pilots. On May 7, 1942, in the Battle of the Coral Sea, fighter pilots from our aircraft carriers Lexington and Yorktown fought the Zero and didn’t know what to call it. Some misidentified it as the German Messerschmitt 109.

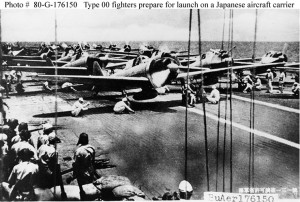

A few weeks later, on June 3 and 4, warplanes flew from the Japanese carriers Ryujo and Junyo to attack the American military base at Dutch Harbor in Alaska’s Aleutian archipelago. Japan’s attack on Alaska was intended to draw remnants of the U.S. fleet north from Pearl Harbor, away from Midway Island, where the Japanese were setting a trap. (The scheme ultimately backfired when our Navy pilots sank four of Japan’s first-line aircraft carriers at Midway, giving the United States a major turning-point victory.)

A few weeks later, on June 3 and 4, warplanes flew from the Japanese carriers Ryujo and Junyo to attack the American military base at Dutch Harbor in Alaska’s Aleutian archipelago. Japan’s attack on Alaska was intended to draw remnants of the U.S. fleet north from Pearl Harbor, away from Midway Island, where the Japanese were setting a trap. (The scheme ultimately backfired when our Navy pilots sank four of Japan’s first-line aircraft carriers at Midway, giving the United States a major turning-point victory.)

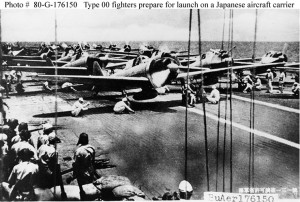

In the raid of June 4, twenty bombers blasted oil storage tanks, a warehouse, a hospital, a hangar, and a beached freighter, while eleven Zeros strafed at will. Chief Petty Officer Makoto Endo led a three-plane Zero section from the Ryujo, whose other pilots were Flight Petty Officers Tsuguo Shikada and Tadayoshi Koga. Koga, a small nineteen-year old, was the son of a rural carpenter. His Zero, serial number 4593, was light gray, with the imperial rising-sun insignia on its wings and fuselage. It had left the Mitsubishi Nagoya aircraft factory on February 19, only three and a half months earlier, so it was the latest design.

Shortly before the bombs fell on Dutch Harbor that day, soldiers at an adjacent Army outpost had seen three Zeros shoot down a lumbering Catalina amphibian. As the plane began to sink, most of the seven-member crew climbed into a rubber raft and began paddling toward shore. The soldiers watched in horror as the Zeros strafed the crew until all were killed. The Zeros are believed to have been those of Endo, Shikada, and Koga.

Shortly before the bombs fell on Dutch Harbor that day, soldiers at an adjacent Army outpost had seen three Zeros shoot down a lumbering Catalina amphibian. As the plane began to sink, most of the seven-member crew climbed into a rubber raft and began paddling toward shore. The soldiers watched in horror as the Zeros strafed the crew until all were killed. The Zeros are believed to have been those of Endo, Shikada, and Koga.

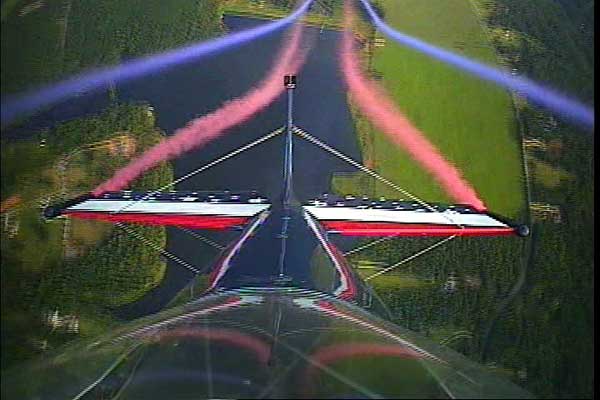

After massacring the Catalina crew, Endo led his section to Dutch Harbor, where it joined the other eight Zeros in strafing. It was then (according to Shikada, interviewed in 1984) that Koga’s Zero was hit by ground fire. An Army intelligence team later reported, “Bullet holes entered the plane from both upper and lower sides.” One of the bullets severed the return oil line between the oil cooler and the engine. As the engine continued to run, it pumped oil from the broken line. A Navy photo taken during the raid shows a Zero trailing what appears to be smoke. It is probably oil, and there is little doubt that this is Zero 4593.

After the raid, as the enemy planes flew back toward their carriers, eight American Curtiss Warhawk P-40s shot down four VaI (Aichi D3A) dive bombers thirty miles west of Dutch Harbor. In the swirling, minutes-long dogfight, Lt. John J. Cape shot down a plane identified as a Zero. Another Zero was almost instantly on his tail. He climbed and rolled, trying to evade, but those were the wrong maneuvers to escape a Zero. The enemy fighter easily stayed with him, firing its two deadly 20-mm cannon and two 7.7-mm machine guns. Cape and his plane plunged into the sea. Another Zero shot up the P-40 of Lt. Winfield McIntyre, who survived a crash landing with a dead engine.

After the raid, as the enemy planes flew back toward their carriers, eight American Curtiss Warhawk P-40s shot down four VaI (Aichi D3A) dive bombers thirty miles west of Dutch Harbor. In the swirling, minutes-long dogfight, Lt. John J. Cape shot down a plane identified as a Zero. Another Zero was almost instantly on his tail. He climbed and rolled, trying to evade, but those were the wrong maneuvers to escape a Zero. The enemy fighter easily stayed with him, firing its two deadly 20-mm cannon and two 7.7-mm machine guns. Cape and his plane plunged into the sea. Another Zero shot up the P-40 of Lt. Winfield McIntyre, who survived a crash landing with a dead engine.

Endo and Shikada accompanied Koga as he flew his oil-spewing airplane to Akutan Island, twenty-five miles away, which had been designated for emergency landings. A Japanese submarine stood nearby to pick up downed pilots. The three Zeros circled low over the green, treeless island. At a level, grassy valley floor half a mile inland, Koga lowered his wheels and flaps and eased toward a three-point landing. As his main wheels touched, they dug in, and the Zero flipped onto its back, tossing water, grass, and gobs of mud. The valley floor was a bog, and the knee-high grass concealed water.

Endo and Shikada circled. There was no sign of life. If Koga was dead, their duty was to destroy the downed fighter. Incendiary bullets from their machine guns would have done the job. But Koga was a friend, and they couldn’t bring themselves to shoot. Perhaps he would recover, destroy the plane himself, and walk to the waiting submarine. Endo and Shikada abandoned the downed fighter and returned to the Ryujo, two hundred miles to the south. (The Ryujo was sunk two months later in the eastern Solomons by planes from the aircraft carrier Saratoga. Endo was killed in action at Rabaul on October 12, 1943, while Shikada survived the war and eventually became a banker.)

Endo and Shikada circled. There was no sign of life. If Koga was dead, their duty was to destroy the downed fighter. Incendiary bullets from their machine guns would have done the job. But Koga was a friend, and they couldn’t bring themselves to shoot. Perhaps he would recover, destroy the plane himself, and walk to the waiting submarine. Endo and Shikada abandoned the downed fighter and returned to the Ryujo, two hundred miles to the south. (The Ryujo was sunk two months later in the eastern Solomons by planes from the aircraft carrier Saratoga. Endo was killed in action at Rabaul on October 12, 1943, while Shikada survived the war and eventually became a banker.)

The wrecked Zero lay in the bog for more than a month, unseen by U.S. patrol planes and offshore ships. Akutan is often foggy, and constant Aleutian winds create unpleasant turbulence over the rugged island. Most pilots preferred to remain over water, so planes rarely flew over Akutan. However, on July 10 a U.S. Navy Catalina (PBY) amphibian returning from overnight patrol crossed the island. A gunner named Wall called, “Hey, there’s an airplane on the ground down there. It has meatballs on the wings.” That meant the rising-sun insignia. The patrol plane’s commander, Lt. William Thies, descended for a closer look. What he saw excited him.

Back at Dutch Harbor, Thies persuaded his squadron commander to let him take a party to the downed plane. No one then knew that it was a Zero. Ens. Robert Larson was Thies’s copilot when the plane was discovered. He remembers reaching the Zero. “We approached cautiously, walking in about a foot of water covered with grass.” Koga’s body, thoroughly strapped in, was upside down in the plane, his head barely submerged in the water. “We were surprised at the details of the airplane,” Larson continues. “It was well built, with simple, unique features. Inspection plates could be opened by pushing on a black dot with a finger. A latch would open, and one could pull the plate out. Wingtips folded by unlatching them and pushing them up by hand. The pilot had a parachute and a life raft.” Koga’s body was buried nearby. In 1947 it was shifted to a cemetery on nearby Adak Island, and later, it is believed, his remains were returned to Japan.

Back at Dutch Harbor, Thies persuaded his squadron commander to let him take a party to the downed plane. No one then knew that it was a Zero. Ens. Robert Larson was Thies’s copilot when the plane was discovered. He remembers reaching the Zero. “We approached cautiously, walking in about a foot of water covered with grass.” Koga’s body, thoroughly strapped in, was upside down in the plane, his head barely submerged in the water. “We were surprised at the details of the airplane,” Larson continues. “It was well built, with simple, unique features. Inspection plates could be opened by pushing on a black dot with a finger. A latch would open, and one could pull the plate out. Wingtips folded by unlatching them and pushing them up by hand. The pilot had a parachute and a life raft.” Koga’s body was buried nearby. In 1947 it was shifted to a cemetery on nearby Adak Island, and later, it is believed, his remains were returned to Japan.

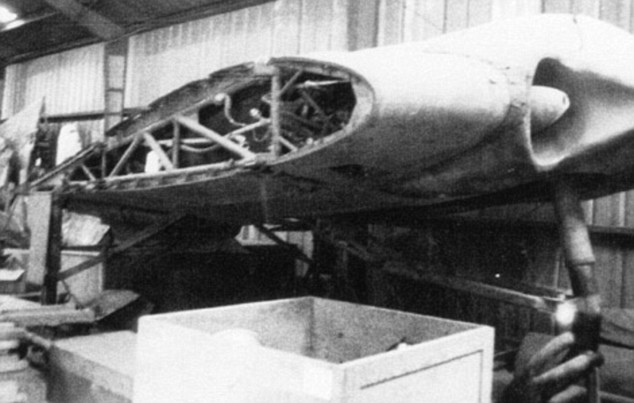

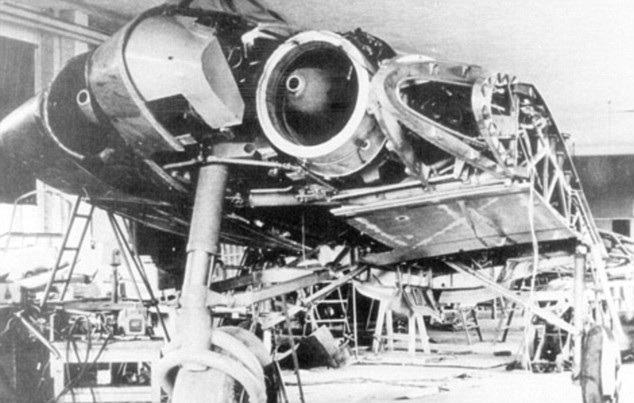

Thies had determined that the wrecked plane was a nearly new Zero, which suddenly gave it special meaning, for it was repairable. However, unlike U.S. warplanes, which had detachable wings, the Zero’s wings were integral with the fuselage. This complicated salvage and shipping. Navy crews fought the plane out of the bog. The tripod that was used to lift the engine, and later the fuselage, sank three to four feet into the mud. The Zero was too heavy to turn over with the equipment on hand, so it was left upside down while a tractor dragged it on a skid to the beach and a barge.

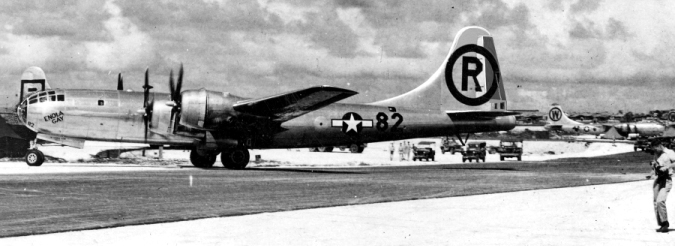

At Dutch Harbor it was turned over with a crane, cleaned, and crated, wings and all. When the awkward crate containing Zero 4593 arrived at North Island Naval Air Station, San Diego, a twelve-foot-high stockade was erected around it inside a hangar. Marines guarded the priceless plane while Navy crews worked around the clock to make it airworthy. (There is no evidence the Japanese ever knew we had salvaged Koga’s plane.)

At Dutch Harbor it was turned over with a crane, cleaned, and crated, wings and all. When the awkward crate containing Zero 4593 arrived at North Island Naval Air Station, San Diego, a twelve-foot-high stockade was erected around it inside a hangar. Marines guarded the priceless plane while Navy crews worked around the clock to make it airworthy. (There is no evidence the Japanese ever knew we had salvaged Koga’s plane.)

In mid-September Lt. Cmdr. Eddie R. Sanders studied it for a week as repairs were completed. Forty-six years later he clearly remembered his flights in Koga’s Zero. “My log shows that I made twenty-four flights in Zero 4593 from 20 September to 15 October 1942,” Sanders told me. “These flights covered performance tests such as we do on planes undergoing Navy tests.”

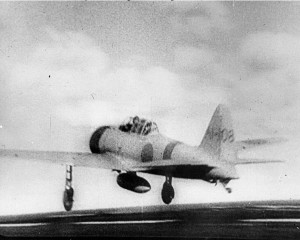

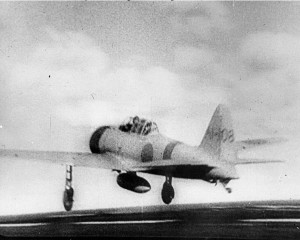

The very first flight exposed weaknesses of the Zero that our pilots could exploit with proper tactics. The Zero had superior maneuverability only at the lower speeds used in dogfighting, with short turning radius and excellent aileron control at very low speeds. However, immediately apparent was the fact that the ailerons froze up at speeds above two hundred knots, so that rolling maneuvers at those speeds were slow and required much force on the control stick. It rolled to the left much easier than to the right. Also, its engine cut out under negative acceleration (as when nosing into a dive) due to its float-type carburetor.

The very first flight exposed weaknesses of the Zero that our pilots could exploit with proper tactics. The Zero had superior maneuverability only at the lower speeds used in dogfighting, with short turning radius and excellent aileron control at very low speeds. However, immediately apparent was the fact that the ailerons froze up at speeds above two hundred knots, so that rolling maneuvers at those speeds were slow and required much force on the control stick. It rolled to the left much easier than to the right. Also, its engine cut out under negative acceleration (as when nosing into a dive) due to its float-type carburetor.

“We now had an answer for our pilots who were unable to escape a pursuing Zero. We told them to go into a vertical power dive, using negative acceleration, if possible, to open the range quickly and gain advantageous speed while the Zero’s engine was stopped. At about two hundred knots, we instructed them to roll hard right before the Zero pilot could get his sights lined up. This recommended tactic was radioed to the fleet after my first flight of Koga’s plane, and soon the welcome answer came back: It works!” Sanders said, satisfaction sounding in his voice even after nearly half a century.

Thus by late September 1942 Allied pilots in the Pacific theater knew how to escape a pursuing Zero. “Was Zero 4593 a good representative of the Model 21 Zero?” I asked Sanders. In other words, was the repaired airplane 100 percent? “About 98 percent,” he replied. The zero was added to the U.S. Navy inventory and assigned its Mitsubishi serial number. The Japanese colors and insignia were replaced with those of the U.S. Navy and later the U.S. Army, which also test-flew it. The Navy pitted it against the best American fighters of the time—the P-38 Lockheed Lightning, the P-39 Bell Airacobra, the P-51 North American Mustang, the F4F-4 Grumman Wildcat, and the F4U ChanceVought Corsair—and for each type developed the most effective tactics and altitudes for engaging the Zero.

Thus by late September 1942 Allied pilots in the Pacific theater knew how to escape a pursuing Zero. “Was Zero 4593 a good representative of the Model 21 Zero?” I asked Sanders. In other words, was the repaired airplane 100 percent? “About 98 percent,” he replied. The zero was added to the U.S. Navy inventory and assigned its Mitsubishi serial number. The Japanese colors and insignia were replaced with those of the U.S. Navy and later the U.S. Army, which also test-flew it. The Navy pitted it against the best American fighters of the time—the P-38 Lockheed Lightning, the P-39 Bell Airacobra, the P-51 North American Mustang, the F4F-4 Grumman Wildcat, and the F4U ChanceVought Corsair—and for each type developed the most effective tactics and altitudes for engaging the Zero.

In February 1945 Cmdr. Richard G. Crommelin was taxiing Zero 4593 at San Diego Naval Air Station, where it was being used to train pilots bound for the Pacific war zone. An SB2C Curtiss Helldiver overran it and chopped it up from tail to cockpit. Crommelin survived, but the Zero didn’t. Only a few pieces of Zero 4593 remain today. The manifold pressure gauge, the air-speed indicator, and the folding panel of the port wingtip were donated to the Navy Museum at the Washington, D.C., Navy Yard by Rear Adm. William N. Leonard, who salvaged them at San Diego in 1945. In addition, two of its manufacturer’s plates are in the Alaska Aviation Heritage Museum in Anchorage, donated by Arthur Bauman, the photographer. Leonard recently told me, “The captured Zero was a treasure. To my knowledge no other captured machine has ever unlocked so many secrets at a time when the need was so great.”

A somewhat comparable event took place off North Africa in 1944—coincidentally on the same date, June 4, that Koga crashed his Zero. A squadron commanded by Capt. Daniel V. Gallery, aboard the escort carrier Guadalcanal, captured the German submarine U-505, boarding and securing the disabled vessel before the fleeing crew could scuttle it. Code books, charts, and operating instructions rescued from U-505 proved quite valuable to the Allies. Captain Gallery later wrote, “Reception committees which we were able to arrange as a result … may have had something to do with the sinking of nearly three hundred U-boats in the next eleven months.” By the time of U-505’s capture, however, the German war effort was already starting to crumble (D-day came only two days later), while Japan still dominated the Pacific when Koga’s plane was recovered.

A somewhat comparable event took place off North Africa in 1944—coincidentally on the same date, June 4, that Koga crashed his Zero. A squadron commanded by Capt. Daniel V. Gallery, aboard the escort carrier Guadalcanal, captured the German submarine U-505, boarding and securing the disabled vessel before the fleeing crew could scuttle it. Code books, charts, and operating instructions rescued from U-505 proved quite valuable to the Allies. Captain Gallery later wrote, “Reception committees which we were able to arrange as a result … may have had something to do with the sinking of nearly three hundred U-boats in the next eleven months.” By the time of U-505’s capture, however, the German war effort was already starting to crumble (D-day came only two days later), while Japan still dominated the Pacific when Koga’s plane was recovered.

A classic example of the Koga plane’s value occurred on April 1, 1943, when Ken Walsh, a Marine flying an F4U Chance-Vought Corsair over the Russell Islands southeast of Bougainville, encountered a lone Zero. “I turned toward him, planning a deflection shot, but before I could get on him, he rolled, putting his plane right under my tail and within range. I had been told the Zero was extremely maneuverable, but if I hadn’t seen how swiftly his plane flipped onto my tail, I wouldn’t have believed it,” Walsh recently recalled. “I remembered briefings that resulted from test flights of Koga’s Zero on how to escape from a following Zero. With that lone Zero on my tail I did a split S, and with its nose down and full throttle my Corsair picked up speed fast. I wanted at least 240 knots, preferably 260. Then, as prescribed, I rolled hard right. As I did this and continued my dive, tracers from the Zero zinged past my plane’s belly.

“From information that came from Koga’s Zero, I knew the Zero rolled more slowly to the right than to the left. If I hadn’t known which way to turn or roll, I’d have probably rolled to my left. If I had done that, the Zero would likely have turned with me, locked on, and had me. I used that maneuver a number of times to get away from Zeros.” By war’s end Capt. (later Lt. Col.) Kenneth Walsh had twenty-one aerial victories (seventeen Zeros, three Vais, one Pete), making him the war’s fourth-ranking Marine Corps ace. He was awarded the Medal of Honor for two extremely courageous air battles he fought over the Solomon Islands in his Corsair during August 1943. He retired from the Marine Corps in 1962 after more than twenty-eight years of service. Walsh holds the Distinguished Flying Cross with six Gold Stars, the Air Medal with fourteen Gold Stars, and more than a dozen other medals and honors.

“From information that came from Koga’s Zero, I knew the Zero rolled more slowly to the right than to the left. If I hadn’t known which way to turn or roll, I’d have probably rolled to my left. If I had done that, the Zero would likely have turned with me, locked on, and had me. I used that maneuver a number of times to get away from Zeros.” By war’s end Capt. (later Lt. Col.) Kenneth Walsh had twenty-one aerial victories (seventeen Zeros, three Vais, one Pete), making him the war’s fourth-ranking Marine Corps ace. He was awarded the Medal of Honor for two extremely courageous air battles he fought over the Solomon Islands in his Corsair during August 1943. He retired from the Marine Corps in 1962 after more than twenty-eight years of service. Walsh holds the Distinguished Flying Cross with six Gold Stars, the Air Medal with fourteen Gold Stars, and more than a dozen other medals and honors.

How important was our acquisition of Koga’s Zero? Masatake Okumiya, who survived more air-sea battles than any other Japanese naval officer, was aboard the Ryujo when Koga made his last flight. He later co-authored two classic books, Zero and Midway. Okumiya has written that the Allies’ acquisition of Koga’s Zero was “no less serious” than the Japanese defeat at Midway and “did much to hasten our final defeat.” If that doesn’t convince you, ask Ken Walsh.

INSIDE THE ZERO

The Zero was Japan’s main fighter plane throughout World War II. By war’s end about 11,500 Zeros had been produced in five main variants. In March 1939, when the prototype Zero was rolled out, Japan was in some ways still so backward that the plane had to be hauled by oxcart from the Mitsubishi factory twenty-nine miles to the airfield where it flew. It represented a great leap in technology. At the start of World War II, some countries’ fighters were open cockpit, fabric-covered biplanes. A low-wing all-metal monoplane carrier fighter, predecessor to the Zero, had been adopted by the Japanese in the mid-1930s, while the U.S. Navy’s standard fighter was still a biplane. But the world took little notice of Japan’s advanced military aircraft, so the Zero came as a great shock to Americans at Pearl Harbor and afterward.

A combination of nimbleness and simplicity gave it fighting qualities that no Allied plane could match. Lightness, simplicity, ease of maintenance, sensitivity to controls, and extreme maneuverability were the main elements that the designer Jiro Horikoshi built into the Zero. The Model 21 flown by Koga weighed 5,500 pounds, including fuel, ammunition, and pilot, while U.S. fighters weighed 7,500 pounds and up. Early models had no protective armor or self-sealing fuel tanks, although these were standard features on U.S. fighters. Despite its large-diameter 940-hp radial engine, the Zero had one of the slimmest silhouettes of any World War II fighter. The maximum speed of Koga’s Zero was 326 mph at 16,000 feet, not especially fast for a 1942 fighter. But high speed wasn’t the reason for the Zero’s great combat record. Agility was. Its large ailerons gave it great maneuverability at low speeds. It could even outmaneuver the famed British Spitfire. Advanced U.S. fighters produced toward the war’s end still couldn’t turn with the Zero, but they were faster and could outclimb and outdive it. Without self-sealing fuel tanks, the Zero was easily flamed when hit in any of its three wing and fuselage tanks or its droppable belly tank. And without protective armor, its pilot was vulnerable.

A combination of nimbleness and simplicity gave it fighting qualities that no Allied plane could match. Lightness, simplicity, ease of maintenance, sensitivity to controls, and extreme maneuverability were the main elements that the designer Jiro Horikoshi built into the Zero. The Model 21 flown by Koga weighed 5,500 pounds, including fuel, ammunition, and pilot, while U.S. fighters weighed 7,500 pounds and up. Early models had no protective armor or self-sealing fuel tanks, although these were standard features on U.S. fighters. Despite its large-diameter 940-hp radial engine, the Zero had one of the slimmest silhouettes of any World War II fighter. The maximum speed of Koga’s Zero was 326 mph at 16,000 feet, not especially fast for a 1942 fighter. But high speed wasn’t the reason for the Zero’s great combat record. Agility was. Its large ailerons gave it great maneuverability at low speeds. It could even outmaneuver the famed British Spitfire. Advanced U.S. fighters produced toward the war’s end still couldn’t turn with the Zero, but they were faster and could outclimb and outdive it. Without self-sealing fuel tanks, the Zero was easily flamed when hit in any of its three wing and fuselage tanks or its droppable belly tank. And without protective armor, its pilot was vulnerable.

In 1941 the Zero’s range of 1,675 nautical miles (1,930 statute miles) was one of the wonders of the aviation world. No other fighter plane had ever routinely  flown such a distance. Saburo Sakai, Japan’s highest-scoring surviving World War II ace, with sixty-four kills, believes that if the Zero had not been developed, Japan “would not have decided to start the war.” Other Japanese authorities echo this opinion, and the confidence it reflects was not, in the beginning at least, misplaced.

flown such a distance. Saburo Sakai, Japan’s highest-scoring surviving World War II ace, with sixty-four kills, believes that if the Zero had not been developed, Japan “would not have decided to start the war.” Other Japanese authorities echo this opinion, and the confidence it reflects was not, in the beginning at least, misplaced.

Today the Zero is one of the rarest of all major fighter planes of World War II. Only sixteen complete and assembled examples are known to exist. Of these, only two are flyable: one owned by Planes of Fame, in Chino, California, and the other by the Confederate Air Force, in Midland, Texas.

I haven’t done the research myself to verify this, but according to something I read not long ago, printer ink is the most expensive commodity on the planet by weight.

I haven’t done the research myself to verify this, but according to something I read not long ago, printer ink is the most expensive commodity on the planet by weight. Manufacturers of other consumer products have caught on to the inkjet business model in which consumables provide the vast majority of the profit. Get enough people buying into that, and they support some other dude’s private jet.

Manufacturers of other consumer products have caught on to the inkjet business model in which consumables provide the vast majority of the profit. Get enough people buying into that, and they support some other dude’s private jet. I like strong coffee. As the rancher-father of a friend reportedly described it, “I’ll be darned if I’m gonna drink a gallon of water to get a single cup of coffee.” Amen, sir.

I like strong coffee. As the rancher-father of a friend reportedly described it, “I’ll be darned if I’m gonna drink a gallon of water to get a single cup of coffee.” Amen, sir. I tried the sample pack that came with the brewer, settled on a few favorite varieties, and ordered some boxes online. It was great . . . until the problems started, problems that apparently have been around with these brewers since 2006 or thereabouts, and which I would have known about if I had only taken the time to do a bit of research.

I tried the sample pack that came with the brewer, settled on a few favorite varieties, and ordered some boxes online. It was great . . . until the problems started, problems that apparently have been around with these brewers since 2006 or thereabouts, and which I would have known about if I had only taken the time to do a bit of research. Since I didn’t know any of this before I bought it, the big surprise came when my brewer began acting up. I Googled “Keurig coffee maker problems” and found a full page of links. Some comments mentioned having gone through as many as five replacement brewers, readily supplied by polite customer service voices. The only catch is the requirement to return the removable K-cup holder assembly from the old unit as “proof of purchase,” although they don’t offer a prepaid postage option for doing that. A minor irritant in the total scheme of things, but in principle it’s still aggravating.

Since I didn’t know any of this before I bought it, the big surprise came when my brewer began acting up. I Googled “Keurig coffee maker problems” and found a full page of links. Some comments mentioned having gone through as many as five replacement brewers, readily supplied by polite customer service voices. The only catch is the requirement to return the removable K-cup holder assembly from the old unit as “proof of purchase,” although they don’t offer a prepaid postage option for doing that. A minor irritant in the total scheme of things, but in principle it’s still aggravating. One comment on the forums indicated a possible solution. A customer studied how the brewer works, and during a failed brew cycle noticed water dribbling out of a 90-degree angled rubber spigot with two holes at upper rear of the water reservoir. He concluded that there was no reason for water to return to the reservoir, asked the simple question of why it was doing that, and focused on the way in which water is delivered from the reservoir to the heated holding tank in the brewer.

One comment on the forums indicated a possible solution. A customer studied how the brewer works, and during a failed brew cycle noticed water dribbling out of a 90-degree angled rubber spigot with two holes at upper rear of the water reservoir. He concluded that there was no reason for water to return to the reservoir, asked the simple question of why it was doing that, and focused on the way in which water is delivered from the reservoir to the heated holding tank in the brewer. At this point, I am flabbergasted that Keurig has been unable to solve a persistent problem with their brewers and can remain in business by sending out replacements. And yes, I understand that customers who aren’t having problems don’t visit forums and there may be many more of them out there than those who are. But the corollary is also logical, that dissatisfied customers simply throw the offending brewers in the trash and go back to their old, reliable Mr. Coffee.

At this point, I am flabbergasted that Keurig has been unable to solve a persistent problem with their brewers and can remain in business by sending out replacements. And yes, I understand that customers who aren’t having problems don’t visit forums and there may be many more of them out there than those who are. But the corollary is also logical, that dissatisfied customers simply throw the offending brewers in the trash and go back to their old, reliable Mr. Coffee.