From news.travel.aol.com:

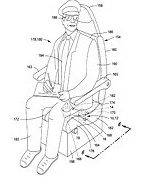

The cockpit of a commercial airplane has a variety of warning systems to help keep pilots out of unsafe situations. In many circumstances, visual and audible indicators will notify a pilot when he needs to take immediate action. Boeing is considering a new method: vibrating the pilot’s seat assembly.

Throughout a flight, pilots do numerous tasks that might not require instant action, but are needed to complete a flight. During longer flights, pilots might get distracted and miss warning indicators that advise them if an action is required, the seat inventors say.

Pilots are also prone to getting sleepy during extended flights. A recent survey conducted for the Norwegian public broadcaster NRK found that out of 389 pilots, 48% said they fell asleep “once” or “rarely” and 2% indicated they fall asleep “often.”

Recently, a Scandinavian Airlines (SAS) Boeing 737 pilot fell asleep mid-flight while the co-pilot was out of the cockpit. In November 2010 an Air India Boeing 737 crashed killing 158 people, which was blamed on a sleep-deprived pilot. [A previous post titled “Troubles in the Cockpit” addressed this accident.]

Boeing is trying to determine if an alert system that uses more than lights and sound could be more effective in keeping fatigued pilots awake during flight. Many aircraft are already designed to shake the control column if a stall is imminent. But with the new seat a pilot would actually feel a vibration thanks to a module mounted under his or her seat.

The Tactile Pilot Alert system patent filed by Boeing and co-authored by chief pilot Frank Santoni, states the vibrating seat would comprise of, “a tactile module that may be mountable to a seat assembly and which may include a vibrating unit and/or a probing unit.”

The Tactile Pilot Alert system patent filed by Boeing and co-authored by chief pilot Frank Santoni, states the vibrating seat would comprise of, “a tactile module that may be mountable to a seat assembly and which may include a vibrating unit and/or a probing unit.”

Presently, Boeing is not giving details on how the system might be used on future planes. “We’re studying the concept, but there are no plans to implement the technology right now,” Doug Alder Jr. with Boeing Communications told AOL Travel News.

I can attest to the fact from personal experience that flying airliners involves long hours of not doing much. Modern technology has created airplanes that with the exception of takeoff, can accomplish any normal required task without control input from the pilots. And by “control input,” I mean good old “stick and rudder” flying with hands and feet coordinated by the computer called the human brain.

For all but a very small percentage of the commercial flight hours spent in the cockpit, pilots serve as systems managers, and the vast majority of those hours is spent at cruise. Other than to monitor what’s going on, pilots are redundant to the automated tasks of maintaining altitude, speed, and course or heading. And the reality is that these hours can be incredibly mind-numbing.

That brings to mind the saying, “Flying airplanes consists of hours and hours of boredom interspersed with moments of stark terror.” Passengers don’t want to think about that, but they intuitively understand that when the terror arrives, they want a top-notch crew up front taking care of business. Think “Miracle on the Hudson.”

And then every once in awhile, something happens to give the flying public a look inside the cockpit that isn’t conducive to getting a “warm fuzzy” back in the cabin. You may remember this:

Northwest pilots overfly destination by 150 miles

Friday, October 23, 2009 3:02 AM by Steve Karnowski, Associated Press

MINNEAPOLIS — The pilots of a Northwest Airlines jet failed to make radio contact with ground controllers for more than an hour and overflew their Minneapolis destination by 150 miles before discovering the mistake and turning around.The plane landed safely at Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport on Wednesday evening, and no one was hurt.

But yesterday, federal officials began investigating whether pilot fatigue was a factor. Keith Holloway, a spokesman for the National Transportation Safety Board, said the agency does not know whether the crew fell asleep, calling that idea “speculative.”

Flight 188, an Airbus A320, was flying from San Diego to Minneapolis with 144 passengers and five crew members. The pilots dropped out of radio contact with controllers just before 7 p.m. CDT, when they were at 37,000 feet. The jet flew over the airport just before 8 p.m. and overshot it before communications were re-established at 8:14 p.m., the NTSB said. The pilots didn’t become aware of their situation until a flight attendant contacted them on the intercom, said a source familiar with the investigation.

The Federal Aviation Administration said the crew members told authorities they became distracted during a heated discussion over airline policy and lost track of their location.

This incident is a perfect example of pilots not taking care of business even in normal circumstances. How hard can this be? The airplane is on autopilot doing all the hard stuff, and other than the passive act of scanning the cockpit frequently to make sure everything is okay, all the crew has to do is listen up.

In this case, flying from California to Minnesota, the airliner would pass through a number of Air Route Traffic Control Centers (ARTCCs), each with a discrete radio frequency for communication. Depending on the amount of traffic in the sector, which varies by location and time of day, the radio can be relatively silent or filled up with transmissons to the point of “not being able to get a word in edgewise.”

Pilots learn to “filter” what they hear over the radio. “American 246, turn right heading 090, descend to and maintain flight level 270” would not be “heard” by the Northwest crew because the transmission doesn’t directly apply to them. And if they are only one hour into the flight, they aren’t expecting to receive instructions to alter course or altitude unless other traffic or weather is a factor. The most likely transmission directed at them would be to change the radio to another frequency as they proceed through different control sectors and regions.

Departing San Diego, the Northwest flight would be directed to contact Los Angeles Center before passing 18,000 feet in the climb, and depending on their route of flight, Salt Lake, Denver, and finally Minneapolis Centers while en route. And within the geographical area controlled by each center, different sectors use different frequencies, so changing the radio is not an infrequent task.

It is, however, a simple one. “Northwest 188, contact Minneapolis on 134.85 good day” should be heard and immediately responded to. In this case, the crew not only failed to hear multiple radio transmissions directed to them, but ignored their planned routing programmed into the navigation system and coupled to the autopilot.

This is only speculation without access to the cockpit voice recorder transcript, but I don’t think the crew was telling the truth about not falling asleep. It’s one thing to be preoccupied with a heated discussion and not hear the radio, but to be awake and completely ignore what the airplane was doing is hard to accept as fact.

This is only speculation without access to the cockpit voice recorder transcript, but I don’t think the crew was telling the truth about not falling asleep. It’s one thing to be preoccupied with a heated discussion and not hear the radio, but to be awake and completely ignore what the airplane was doing is hard to accept as fact.

The flight plan being followed by the autopilot had no navigation fixes to the east of Minneapolis. I’ve never flown the Airbus A320, but my educated guess is that when this airplane reached the point that the autopilot didn’t know what to do next, it did what is was designed to do, maintain heading and altitude. This means that the crew was so engrossed in their conversation that the effects of their inattention began long before arriving overhead their destination.

Crews don’t “slam dunk” airliners during the descent to landing. From the average cruise altitude on a flight of 1500 miles, the “top of descent” for the Airbus would have been about 100 miles to the west of Minneapolis. They flew 150 miles east. To cruise for 250 miles while oblivious to the real world outside the cockpit is truly astonishing.

Crews don’t “slam dunk” airliners during the descent to landing. From the average cruise altitude on a flight of 1500 miles, the “top of descent” for the Airbus would have been about 100 miles to the west of Minneapolis. They flew 150 miles east. To cruise for 250 miles while oblivious to the real world outside the cockpit is truly astonishing.

I have no idea if Boeing engineers had this incident in mind when they brainstormed the idea of a vibrating cockpit seat, but I wonder if they’ve ever heard of vibrating beds? I can hear it now, the last communication on the cockpit voice recorder between the captain and the first officer:

“You got any quarters?”

One Response to Goodnight in the Cockpit