Camouflage is an essential component of survival in combat, and the objective is to eliminate visual contrast. Foot soldiers wear different camouflage clothing for jungle, desert, and arctic conditions. Snipers employ the ghillie suit to blend into the surrounding environment. Aircraft are painted in mottled patterns on the upper surface to conceal their shape from the prying eyes of an airborne enemy above, and white, pale blue, or gray to make it more difficult for a ground-based enemy to acquire and maintain visual contact. Unfortunately, early warning and weapons system radars don’t care about any of that.

Camouflage is an essential component of survival in combat, and the objective is to eliminate visual contrast. Foot soldiers wear different camouflage clothing for jungle, desert, and arctic conditions. Snipers employ the ghillie suit to blend into the surrounding environment. Aircraft are painted in mottled patterns on the upper surface to conceal their shape from the prying eyes of an airborne enemy above, and white, pale blue, or gray to make it more difficult for a ground-based enemy to acquire and maintain visual contact. Unfortunately, early warning and weapons system radars don’t care about any of that.

During WWII, one of the most significant flaws of the German high command during the Battle of Britain was failure to appreciate the role of British radar in the RAF’s ability to manage a vastly outnumbered fighter force effectively enough to survive a bloody struggle of attrition. And in a classic case of a day late and a dollar short, it turns out that the Luftwaffe had within its grasp a weapon that might have altered the course of history.

A friend sent me these pictures and text, and I have to admit that at first glance, I thought it might be another case of someone using Photoshop trickery to alter the appearance of an airplane as I described in a previous post on this site titled “The Most Amazing Airplane in History.” To the contrary, the Horten Ho 2-29 represents another example of the technological gap between the inventiveness of German engineering in the 1940s and that of the Allies.

It has long been recognized that Germany’s technological expertise during the war was years ahead of the competition. The list is ominously impressive: the Panzer tank, V-1 and V-2 rockets, ME-262 jet fighter, extensive research into nuclear fission, and in the case of the Ho 2-29, a stealth bomber nearly 40 years prior to the Lockheed F-117 Nighthawk. With its smooth and elegant lines, this “flying wing” design could be a prototype for some future successor to the current-day stealth bomber. Fortunately for the Allies, the Germans were not able to build the aircraft on an industrial scale before the invasion of Europe.

Depending on the accuracy of the source, history can only show us what actually happened. But that’s never prevented historians from taking a hypothetical next step. In the case of WWII, it is clear that Hitler was at the same time a master of manipulation and an abject failure as supreme commander of German armed forces. His disregard of the advice of senior military commanders and critical unilateral decisions at multiple times throughout the war can be directly traced to the ultimate fall of the Third Reich. We can only guess at how different the outcome of the war might have been if he had listened to his generals, but one thing is certain: German ingenuity was way ahead of its time.

By 1943, Nazi high command feared the war was beginning to turn against them, and they were desperate to develop new weapons. Nazi bombers were suffering badly when faced with the speed and maneuverability of the Spitfire and other Allied fighters. Luftwaffe chief Hermann Goering demanded that designers come up with a bomber that would meet his requirements, one that could carry 2200 lbs over 600 miles flying at 600 mph.

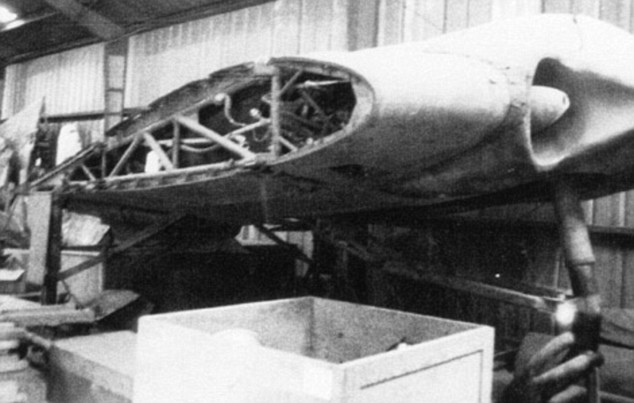

Two pilot brothers in their thirties, Reimar and Walter Horten, were inspired to design the Ho 2-29 by the deaths of thousands of Luftwaffe pilots in the Battle of Britain. They suggested a flying wing design they had been working on for years. In theory, the flying wing was very efficient because it minimized drag, and the brothers were convinced that such a plane would meet Goering’s requirements with very high speeds in a dive and an incredibly long range.

Two pilot brothers in their thirties, Reimar and Walter Horten, were inspired to design the Ho 2-29 by the deaths of thousands of Luftwaffe pilots in the Battle of Britain. They suggested a flying wing design they had been working on for years. In theory, the flying wing was very efficient because it minimized drag, and the brothers were convinced that such a plane would meet Goering’s requirements with very high speeds in a dive and an incredibly long range.

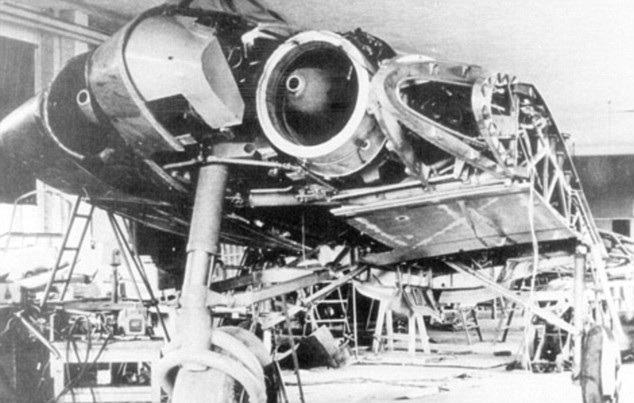

Construction on a prototype was begun in Goettingen in Germany in 1944. Hitler’s engineers only made three, and conducted tests by dragging them behind a glider. The centre pod was made from a welded steel tube, and was designed to be powered by a BMW 003 engine. The 142-foot wingspan bomber was submitted for approval in 1944, and it would have exceeded Goering’s requirements by a huge margin: Berlin to NYC and back without refueling, thanks to the blended wing design and six BMW 003A or eight Junker Jumbo 004B turbojets. Hitler was desperate for a way to strike the United States, and the Ho 2-29 would have really tickled his Teutonic fancy.

But the most important innovation was Reimar Horten’s idea to coat the aircraft in a mix of charcoal dust and wood glue. He thought that the electromagnetic waves of radar would be absorbed by the high graphite content of the paint, and in conjunction with the aircraft’s sculpted surfaces, the craft would be rendered almost invisible to radar detectors. This was, as a matter of fact, the same method

eventually used by the U.S. in the early 1980s with the F-117A Nighthawk.

After the war, the Americans captured the prototype Ho 2-29s along with the blueprints and used some of the German technological advances to aid their own designs. But experts always doubted claims that the Horten could actually function as a stealth aircraft. Using the blueprints and the only remaining prototype craft, Northrop-Grumman (the defense firm behind the B-2) has built a full-size replica of a Horten Ho 2-29 with materials available in the 40s.

It took Northrop 2,500 man-hours and $250,000 to construct a non-flying replica that was radar-tested by placing it on a 50-foot articulating pole and exposing it to electromagnetic waves. The tests proved that the aircraft is not completely invisible to the type of radar used in the war. But thanks to the use of wood and carbon, jet engines integrated into the fuselage with intakes years ahead of their time, and its blended surfaces, the Ho 2-29 could have been over London eight minutes after the British early warning radar system detected it and well before RAF fighters could be scrambled to intercept.

Experts are now convinced that given a bit more time, mass deployment of this aircraft could have changed the course of the war. Luckily for Britain and possibly the world, the Horten flying wing fighter-bomber never got much further than the blueprint and prototype stage.

The research was filmed for a forthcoming documentary on the National Geographic Channel.

2 Responses to I Can’t See You