Twilight: [figurative] a period or state of gradual decline.

As a career military officer and history buff, I really enjoy reading books that take a close and detailed look at significant events in the history of war. The Twilight Warriors by Robert Gandt focuses on the closing months of WWII as described on the jacket: For 95 days in 1945, half a million Americans and Japanese clashed in the largest land-air-sea engagement in history. Okinawa was the last — and bloodiest — battle of the Pacific war. This is the story of the men who fought it.

As a career military officer and history buff, I really enjoy reading books that take a close and detailed look at significant events in the history of war. The Twilight Warriors by Robert Gandt focuses on the closing months of WWII as described on the jacket: For 95 days in 1945, half a million Americans and Japanese clashed in the largest land-air-sea engagement in history. Okinawa was the last — and bloodiest — battle of the Pacific war. This is the story of the men who fought it.

No one on either side of the conflict doubts the eventual outcome. For a tightly knit band of naval aviators just out of training, and who call themselves Tail End Charlies, the greatest worry is that the war will end before they have a chance to face the enemy. Opposing them are the “young gods,” honor-bound Japanese airmen dedicated to the tradition of the classic samurai warrior, and who volunteer for one-way missions known as kamikaze.

Despite the flood of propaganda directed by the Japanese military at their own countrymen promising a final glorious victory, and at American service members warning of defeat and death on the island of Okinawa, the only realistic Japanese objective was to avoid the disgrace of unconditional surrender with a negotiated cessation of hostilities. And the tactic for achieving this outcome was very simple: kill enough Americans to convince the United States that the death toll suffered during the invasion of Japan would be far too high a price.

It very nearly worked: 12,250 Americans killed or missing, another 36,631 wounded. Among them were 4,907 Navy men with almost as many wounded. Thirty-four Allied ships were sunk and 368 damaged, with 763 aircraft lost, making Okinawa the costliest naval engagement in U.S. history.

Gandt provides a vivid account of the underlying reasons behind this horrific carnage from both sides of the conflict. Inter-service distrust and rivalries among the U.S. military leaders lengthened the ground battle, augmented by the decision of the senior Japanese commander to put aside the Samurai tradition of glorious death in a banzai charge and conduct a brilliant campaign of carefully planned mini-retreats. The longer the land battle raged, the longer the U.S. fleet surrounding Okinawa remained within easy striking distance of airfields in the Japanese home islands. Like killer bees, the kamikazes swarmed.

Based on the battle for Okinawa, estimates put the projected American death toll during the invasion of Japan at more than a million. In the years since, debate has continued over whether the decision to use the atomic bomb was in fact necessary to end the war in the Pacific. My purpose here is not to address that issue, only to share in this Visitor Stories logbook another example of an aviator’s “office” through the “magic” of 360-degree panoramic photography.

Based on the battle for Okinawa, estimates put the projected American death toll during the invasion of Japan at more than a million. In the years since, debate has continued over whether the decision to use the atomic bomb was in fact necessary to end the war in the Pacific. My purpose here is not to address that issue, only to share in this Visitor Stories logbook another example of an aviator’s “office” through the “magic” of 360-degree panoramic photography.

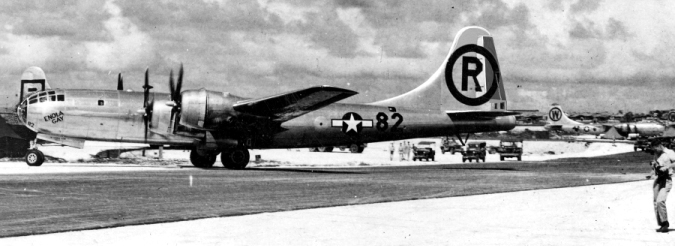

Col. Paul W. Tibbets sat in the cockpit of this B-29 Superfortress named after his mother, Enola Gay Tibbets, and on August 6, 1945, dropped the first atomic bomb code-named “Little Boy” on the city of Hiroshima, Japan. The link below puts you there and allows you to take a tour by “moving the lens” 360 degrees with your pointer, up and down, and to zoom in and out. As you do, think about one man at work in this office, the boss of a crew of ten other airmen, on a mission that changed the world forever.

One Response to Not Just Another Day at Work