We continue with the six-part series to showcase some of the finest paintings depicting significant events in the WWII air war:

Bound for Tokyo, Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Doolittle launches his B-25 Mitchell from the heaving deck of the carrier USS Hornet on the morning of 18 April, 1942. Leading a sixteen-bomber force on their long-distance one-way mission, the Doolittle Raiders completed the first strike at the heart of Imperial Japan since the infamous attack on Pearl Harbor four months earlier. Together, they completed one of the most audacious air raids in aviation history.

Bound for Tokyo, Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Doolittle launches his B-25 Mitchell from the heaving deck of the carrier USS Hornet on the morning of 18 April, 1942. Leading a sixteen-bomber force on their long-distance one-way mission, the Doolittle Raiders completed the first strike at the heart of Imperial Japan since the infamous attack on Pearl Harbor four months earlier. Together, they completed one of the most audacious air raids in aviation history.

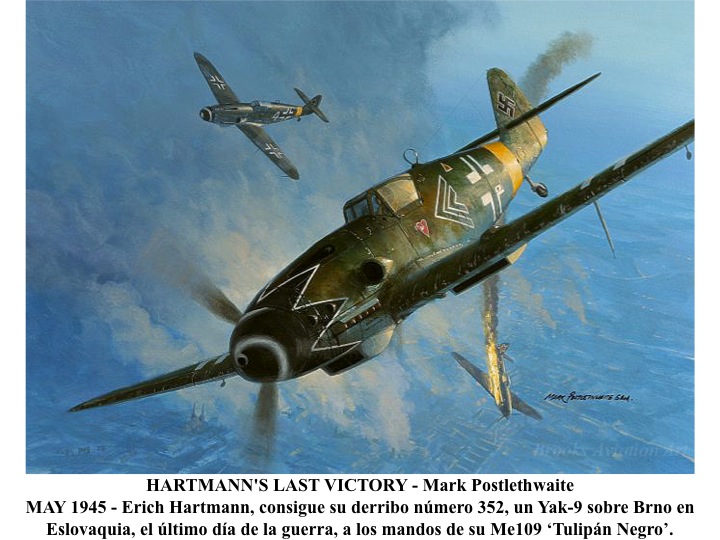

The highest scoring fighter pilot in history, Erich Hartmann shoots down his last victim, his 352nd, a Soviet Yak-9 Fighter over Brno in Slovakia. Hartmann is depicted here piloting his Messerschmitt ME109 “Black Tulip”, on 8 May 1945, the last day of the war.

The highest scoring fighter pilot in history, Erich Hartmann shoots down his last victim, his 352nd, a Soviet Yak-9 Fighter over Brno in Slovakia. Hartmann is depicted here piloting his Messerschmitt ME109 “Black Tulip”, on 8 May 1945, the last day of the war.

“Bogies, 11 o’clock high!” shouted Lt. Doug Canning, breaking a two-hour radio silence. Maj. John Mitchell had led sixteen P-38’s of his 339th fighter Squadron from Guadalcanal’s Henderson Field to Bougainville on 18 April 1943 to intercept the Betty bomber carrying Japanese Imperial Combined Fleet commander Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto. Now, after flying 400 miles at 50 feet above the water, navigating by pure dead-reckoning, the flight sighted two Betty bombers escorted by six Zeroes descending toward Ballale Island.

“Bogies, 11 o’clock high!” shouted Lt. Doug Canning, breaking a two-hour radio silence. Maj. John Mitchell had led sixteen P-38’s of his 339th fighter Squadron from Guadalcanal’s Henderson Field to Bougainville on 18 April 1943 to intercept the Betty bomber carrying Japanese Imperial Combined Fleet commander Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto. Now, after flying 400 miles at 50 feet above the water, navigating by pure dead-reckoning, the flight sighted two Betty bombers escorted by six Zeroes descending toward Ballale Island.

Maj. Mitchell and twelve Lightnings climbed to provide high cover while Capt. Tom Lanphier and Lts. Rex Barber, Frank Holmes, and Ray Hine, designated “attack flight,” turned to intercept the bombers. As they climbed toward the Bettys, Lanphier saw three Zeroes diving to defend the bombers and turned sharply into the lead fighter, leaving Barber to continue the attack on the bomber.

Curving in behind the lead bomber, Barber raked the descending Betty from wingtip to wingtip. Thick black smoke began to stream from the right engine and the bomber snapped to the left. Moments later it sliced into the jungle, the crash site marked by a rising column of black, oily smoke.

Turning toward the coast, Barber finished off the second Betty now under attack by Frank, and downed a Zero that had belatedly joined the battle from nearby Kahili Airdrome. Shortly after, Mitchell called “Mission accomplished!” and fifteen Lightnings turned toward Guadalcanal. Lt. Ray Hine, last seen skimming the water with smoke trailing from his engine, did not return from the mission and was never found.

This extraordinary interception, executed by P-38’s based near Guadalcanal, was made possible through radio interception and signal decryption efforts by Navy intelligence facilities at Pearl Harbor and other Pacific locations.

The German Me 262 jet fighters, used primarily to attack USAAF heavy bomber formations in early 1945, were very vulnerable to fighter attacks during take-off and landing. The Allies had therefore adapted a strategy of having fighters patrol in the vicinity of Me262 bases, waiting for the return of the German jets from their missions. These ambushes soon proved highly effective, with the Luftwaffe losing many jets to the guns of the USAAF.

The German Me 262 jet fighters, used primarily to attack USAAF heavy bomber formations in early 1945, were very vulnerable to fighter attacks during take-off and landing. The Allies had therefore adapted a strategy of having fighters patrol in the vicinity of Me262 bases, waiting for the return of the German jets from their missions. These ambushes soon proved highly effective, with the Luftwaffe losing many jets to the guns of the USAAF.

To counteract the mounting losses, special units were formed, equipped with the Focke-Wulf 190 D-9 (“Dora Neun”), regarded by many as the Luftwaffe’s finest piston-engined fighter of the war. Manned by experienced veterans of JG52 and JG54, they were tasked with providing top cover for the jets at their airfields at Munich, and Ainring near Salzburg.

In order to make these aircraft clearly discernible to the German anti-aircraft gunners, their undersides were painted red with white stripes, thus the legend of the “parrot wing” was born. One of this unit’s elements was the so-called “strangler swarm” led by Lt. Heino Sachsenberg.

Here we see Sachsenberg in his Focke Wulf 190 Dora 9 “Rote 1” W.Nr. 600424, as he turns into P-51s over the airfield of Ainring in an attempt to protect the approaching jet fighters from the Mustangs’ attack.

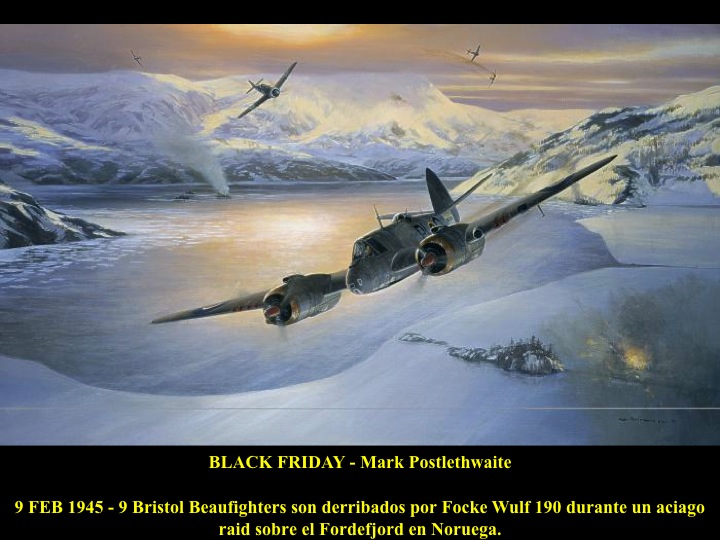

At 1400 hours on the 9th February 1945, 31 Bristol Beaufighters of 445 (RAAF), 404(RCAF) and 144 Squadron (RAF) took off for a strike against a small German Naval Force hidden in Fordefjord. By 1900 hours that evening, 404 Squadron were coming to terms with the loss of six of their aircraft, 11 men dead and one POW. In total, nine Bristol Beaufighters were lost that day along with one North American Mustang. The Germans lost 5 Focke Wulf 190s. Fourteen Allied aircrew and two German pilots were dead.

It is late summer, 1940, and the Battle of Britain is at its height. Racing for the coast following a bombing mission over southern England, a straggling He111 of KG55 has been attacked by a Spitfire of RAF Fighter Command. The bomber is badly damaged, but in the nick of time a pair of Me109s of JG26 come to the rescue, sending the Spitfire diving into the Channel. If they are lucky the Heinkel crew may still make it back to their base in France.

It is late summer, 1940, and the Battle of Britain is at its height. Racing for the coast following a bombing mission over southern England, a straggling He111 of KG55 has been attacked by a Spitfire of RAF Fighter Command. The bomber is badly damaged, but in the nick of time a pair of Me109s of JG26 come to the rescue, sending the Spitfire diving into the Channel. If they are lucky the Heinkel crew may still make it back to their base in France.

On the morning of May 25, 1944, three pilots from the 4th Fighter Group, the “Debden Eagles,” 336th Fighter Squadron, 8th Air Force, were over Germany looking for trouble. Flying near Botenheim, they encountered German planes from III JG1, 9th Staffel.

On the morning of May 25, 1944, three pilots from the 4th Fighter Group, the “Debden Eagles,” 336th Fighter Squadron, 8th Air Force, were over Germany looking for trouble. Flying near Botenheim, they encountered German planes from III JG1, 9th Staffel.

During the ensuing dogfight, a Messerschmitt Bf109G-6/AS (also known as an Ausburg Eagle) came up behind Captain Joseph H. Bennett’s P-51B Mustang while staying below the P-51’s propeller gust.

The Bf109’s guns jammed, but the young Luftwaffe pilot, Oberfähnrich Hubert Heckmann, was determined not to let the American flyer get away. Heckmann pulled up to the P-51’s height and rammed his Bf109 fighter into the tail of Bennett’s aircraft.

The impact sheared off the tail and rear fuselage section and came within a few feet of the rear fuselage tank.

With his aircraft’s nose thrust skyward, Bennett bailed out near Botenheim. Going into a loop, the P-51 crashed into a house in the middle of the village. His own plane seriously damaged, Heckmann managed to make a belly crash landing.

Bennett, a former RAF Eagle Squadron pilot, was captured and taken to a jail by German military officials. Heckmann later came to introduce himself and meet the first American flier he had put out of commission. Bennett remain a German prisoner until the end of the war. The 336th Fighter Squadron lost another Mustang in this fight but made claims of shooting down five of the enemy.

After the war, the two airmen became friends and met every year for their reunion.

Led by Squadron Commander Roland “Bee” Beamont, Hawker Typhoons of 609 Squadron are dramatically illustrated as they scramble from their base at Manston in April 1943.

Led by Squadron Commander Roland “Bee” Beamont, Hawker Typhoons of 609 Squadron are dramatically illustrated as they scramble from their base at Manston in April 1943.

This image is the 25-foot high by 75-foot wide mural in the World War II Gallery of the National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

This image is the 25-foot high by 75-foot wide mural in the World War II Gallery of the National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

The B-17G, 42-38050, “Thunder Bird” of the 303rd Bomb Group, based at Molesworth, England, is seen at 11:45 AM, 15 August 1944, over Trier, Germany, on its return to base from a mission to Weisbaden. B-17Gs “Bonnie B,” “Special Delivery,” and “Marie” are seen below as a Messerschmitt 109G and Focke Wulf FW 190 attack Thunder Bird’s element.

Jeff Ethell’s research for the mural revealed the names and aircraft identities of all U.S. and many German participants in this battle in which the 303rd lost nine Fortresses in this attack by Luftwaffe fighters.

Please be on the lookout for Part Four of “Beautiful Aviation Art.”