Over 85% of all aircraft accidents aren’t really accidental because the chain of events leading up to the crash includes some degree of pilot error. One all-too-common cause of these crashes is a disease known as “get-home-itis.”

The following account is adapted with selected editing from the online magazine of the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA). The original article is titled, “Personal pressure: Weather dooms pilot anxious to get home” by David Kenny.

The following account is adapted with selected editing from the online magazine of the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA). The original article is titled, “Personal pressure: Weather dooms pilot anxious to get home” by David Kenny.

Patience is an essential survival skill for pilots. Sometimes conditions just don’t cooperate, and it doesn’t matter how badly you need to be on your way. Long-term success—not to mention survival—requires learning that if the weather was unflyable yesterday, that same weather will still be unflyable today. This gets easier to accept as reality with experience, but in extreme cases even the most seasoned pilots may struggle to keep themselves on the ground until circumstances improve.

At 10:18 a.m. on Jan. 4, 2010, a Cessna 172 took off from Bangor International Airport in Maine bound for Goose Bay, Newfoundland, on the first leg of a transatlantic crossing en route to eventual delivery to a buyer in Russia. Thirty-six minutes later it crashed through the ice on the Penobscot River, killing the solo pilot.

At 10:18 a.m. on Jan. 4, 2010, a Cessna 172 took off from Bangor International Airport in Maine bound for Goose Bay, Newfoundland, on the first leg of a transatlantic crossing en route to eventual delivery to a buyer in Russia. Thirty-six minutes later it crashed through the ice on the Penobscot River, killing the solo pilot.

The pilot’s IFR (instrument flight rules) flight plan estimated an unusual seven-and-a-half hours time en route (due to “ferry tanks” that increased the fuel capacity of the 172). Conditions were not especially favorable for a long cross-country: northwest winds gusting to 17 knots and an altimeter setting of 29.35 (very low pressure and indicative of lousy weather), with overcast ceilings at 2,600 feet above ground level (agl), and a temperature of 3 degrees Celsius (just above freezing at the surface).

Two witnesses reported mist and light snow at the time of departure, and the warning of STRUCTURAL ICE should have jumped off the weather report and grabbed the pilot around the throat. But it didn’t, and he departed Bangor as planned.

Two witnesses reported mist and light snow at the time of departure, and the warning of STRUCTURAL ICE should have jumped off the weather report and grabbed the pilot around the throat. But it didn’t, and he departed Bangor as planned.

At 10:40 a.m., the pilot was handed off to the Boston Air Route Traffic Control Center (ARTCC) and reported climbing through 6,000 feet mean sea level (msl) for his filed altitude of 9,000. A few seconds later he requested clearance to level at 7,000 feet, which was approved.

Five minutes after that, the controller asked if he was in fact going to climb to 7,000 and was told the Skyhawk’s rate of climb was down to fifty feet per minute. The pilot requested clearance to level off at 6,000 to build up airspeed. He did not specifically mention icing but did add that he was “a bit heavy.”

That was certainly true. At Bangor he’d filled the 124-gallon ferry tank as well  as the wing tanks. This brought the airplane’s weight close to the maximum allowed under the special airworthiness certificate issued by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) for the ferry flight, which was 30 percent above the maximum authorized for an unmodified 172. This is a crucial factor contributing to what happened.

as the wing tanks. This brought the airplane’s weight close to the maximum allowed under the special airworthiness certificate issued by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) for the ferry flight, which was 30 percent above the maximum authorized for an unmodified 172. This is a crucial factor contributing to what happened.

Extra weight robs airplanes of performance in any flight regime. The Cessna 172 isn’t known for its high rate of climb even under ideal conditions. And although the pilot had FAA approval to takeoff at the higher gross weight, his aircraft performance didn’t care.

About three minutes later, the Boston controller transmitted that “it appears you’re having a hard time maintaining altitude. My minimum IFR altitude in your area is three thousand seven hundred.” This transmission clearly indicates the controller’s concern that the pilot was descending rather than climbing to his assigned altitude of 6,000 feet.

The Cessna pilot then replied, “. . . some severe turbulence here . . . I’m, uh, having control difficulties.” The controller asked whether he’d like to return to Bangor, and contacted Approach Control to coordinate the emergency after the pilot agreed.

The pilot established radio contact with Approach at 10:53 a.m. After reading back a clearance direct to the navigation fix to begin his instrument approach, the pilot added that he was “in extreme turbulence with over ninety-degree banks.”

The pilot established radio contact with Approach at 10:53 a.m. After reading back a clearance direct to the navigation fix to begin his instrument approach, the pilot added that he was “in extreme turbulence with over ninety-degree banks.”

A minute and a half after he reported trying to maintain 2,300 feet msl, radar contact was lost. The last altitude recorded on radar indicated the Skyhawk at 1,200 feet. The first reports of an ELT (emergency locator transmitter) signal came in ten minutes later, barely three minutes before the local fire department called Bangor Tower to report the crash. Most of the airplane was found submerged, making it impossible to confirm that it had accumulated ice, but this seems the likeliest explanation for its rapid descent.

The 77-year-old commercial pilot had more than 14,000 hours of flight experience, including 9,500 in single-engine airplanes and about 2,000 in actual instrument conditions. He was highly regarded by the company hired to arrange the ferry flight, for which he had worked as a contract pilot on other occasions. When he filed his flight plan, he told the briefer that he was aware of cautions for widespread instrument flight conditions, moderate turbulence below 11,000 feet, moderate icing below 13,000 feet, with freezing levels of 2,500 feet and below.

Why did an experienced professional pilot choose to launch in these conditions? To do so required that he ignore two critical limitations: 1) the 172 was not equipped with icing protection, which means that intentional flight into known icing was strictly prohibited, and 2) the special airworthiness certificate issued for his flight by the FAA included the direction to “avoid moderate to severe turbulence.”

The investigation turned up some hints. The pilot had told the Flight Service  briefer that he’d been “stuck for a week here.” Two witnesses at the airport recalled his telling them how anxious he was to return to Britain, where his daughter was scheduled to undergo surgery and his wife had recently had an automobile accident. The bad weather had frustrated him to the point of considering leaving the Cessna and flying home commercially.

briefer that he’d been “stuck for a week here.” Two witnesses at the airport recalled his telling them how anxious he was to return to Britain, where his daughter was scheduled to undergo surgery and his wife had recently had an automobile accident. The bad weather had frustrated him to the point of considering leaving the Cessna and flying home commercially.

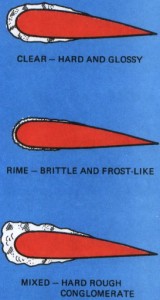

But he didn’t, and this crash illustrates the deadly consequences of the pilot’s failure to use even a modicum of common sense and good judgment. His airplane was overloaded. Its normally anemic climb rate was further compromised by the additional weight. He could not possibly avoid icing conditions along his route of flight. He knew that structural ice exacts a double penalty on airplanes by increasing weight and destroying lift by disrupting airflow over the wings and flight controls. His airplane had no way to prevent structural icing or remove it once it had formed.

Yet in the face of all those factors clearly indicating need for caution, he succumbed to get-home-itis and paid the ultimate price.