I would rather hit myself in the thumb with a hammer than try to write a compelling, evocative blurb about my novel. I realize saying

I would rather hit myself in the thumb with a hammer than try to write a compelling, evocative blurb about my novel. I realize saying  that sets me up for a reader to reply, “That would require your novel to be compelling and evocative,” but I’ll ignore the possibility to speculate on why something that looks so easy can be so hard.

that sets me up for a reader to reply, “That would require your novel to be compelling and evocative,” but I’ll ignore the possibility to speculate on why something that looks so easy can be so hard.

![]() Walk into any bookstore and randomly consider any dust jacket description. It either captures your interest so you’ll plop down the bucks and take it home, or it doesn’t. The difference between the two probably has more to do with what the blurb says than how it says it. That’s because there’s a proven structural “formula” for success, certain key elements that create effective advertising.

Walk into any bookstore and randomly consider any dust jacket description. It either captures your interest so you’ll plop down the bucks and take it home, or it doesn’t. The difference between the two probably has more to do with what the blurb says than how it says it. That’s because there’s a proven structural “formula” for success, certain key elements that create effective advertising.

One of the “how to write a pitch” suggestions is to spend time reading a bunch of them. I’ve done that, ended up excited about trying it for my novel, sat down at the computer and stared at a blank screen for an hour before deciding to try again another day. What’s up with that?

The only answer I can come up with is that it requires a totally different set of skills than those required to create the novel. That’s not to say I can’t learn how to do it, but that writing the novel hasn’t prepared me in advance.

The only answer I can come up with is that it requires a totally different set of skills than those required to create the novel. That’s not to say I can’t learn how to do it, but that writing the novel hasn’t prepared me in advance.

I’m just speculating, but excessive familiarity might have something to do with it. If we assume that whoever writes jacket copy for a novel has read it, it’s reasonable to assume the person has read it only once. Maybe that facilitates being able to step back far enough to condense the story idea into a relatively few number of sentences.

And maybe one of the reasons I can’t do that easily is that I’ve spent so much time with it, enough to complete over 13 drafts as I struggle to improve both the story and my ability to tell it effectively. I’ve nearly memorized every word, and to condense 100,000 of them into 300 or less is like slaughtering the other 97,700. Did I mention how hard that’s been?

In my first post on this topic, I compared the pitch for the ABNA contest to a query letter for submitting to agents. Since then, I’ve confirmed that round one does in fact narrow the field based upon the pitch alone, from a maximum of 5000 entries in each of the two categories to a maximum of 1000 in each.

In my first post on this topic, I compared the pitch for the ABNA contest to a query letter for submitting to agents. Since then, I’ve confirmed that round one does in fact narrow the field based upon the pitch alone, from a maximum of 5000 entries in each of the two categories to a maximum of 1000 in each.

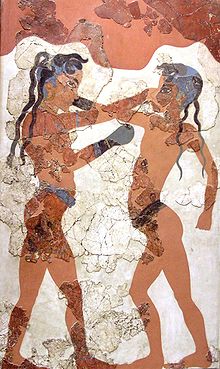

I have no illusions about my chances of making the cut by being in the top 20% in my category, which includes everything except young adult. That bundles a wide variety of fiction together into a boxing match refereed by what has to be a similarly wide variety of individual judges. I can only hope that Amazon has avoided selecting evaluators with personal bias, such as that based upon mainstream literary versus commercial genre fiction. Unless, of course, the first-round judge I draw loves to read mysteries and is fascinated with aviation topics.

I have no illusions about my chances of making the cut by being in the top 20% in my category, which includes everything except young adult. That bundles a wide variety of fiction together into a boxing match refereed by what has to be a similarly wide variety of individual judges. I can only hope that Amazon has avoided selecting evaluators with personal bias, such as that based upon mainstream literary versus commercial genre fiction. Unless, of course, the first-round judge I draw loves to read mysteries and is fascinated with aviation topics.

I may, however, have found within the multiple pages of contest information something to ease my concerns in this regard. The first-round selection criteria based on the pitch are: originality of idea, overall strength of pitch, and the quality of the writing. That seems fair enough, and hopefully the judges are tuned in to only those three evaluation factors.

It’s also informative to note that comments on the ABNA forum point out the role of pure luck. Contestants have said that the same pitch that passed muster on the first round one year resulted in a knockout the next year, and vice versa. It appears that all I can do is enter the ring with my best punch.

Which brings me back to putting on the gloves, and I need to get back to work on my latest version to see if it still carries the power as well as I thought it did last night.

Which brings me back to putting on the gloves, and I need to get back to work on my latest version to see if it still carries the power as well as I thought it did last night.

I’m not optimistic, however. I’ve written five versions so far, and each time it’s like another round with a heavyweight.

Before the contest entry deadline, I’m hoping to have written the pitch with a punch.

Odds, anyone?

One Response to ABNA – The Pitch