The following is extracted from official records of the National Transportation Safety Board and is slightly edited for brevity:

“On February 12, 2009, a Colgan Air, Inc., Bombardier DHC-8-400, operating as Continental Connection flight 3407, was on a night instrument approach to Buffalo-Niagara International Airport, Buffalo, New York, when it crashed into a residence in Clarence Center, New York, about five nautical miles northeast of the airport. The two pilots, two flight attendants, and 45 passengers aboard the airplane were killed, one person on the ground was killed, and the airplane was destroyed by impact forces and a post-crash fire. Weather conditions at the time of the accident included a wintry mix of icing, snow, fog, and gusty winds.

“On February 12, 2009, a Colgan Air, Inc., Bombardier DHC-8-400, operating as Continental Connection flight 3407, was on a night instrument approach to Buffalo-Niagara International Airport, Buffalo, New York, when it crashed into a residence in Clarence Center, New York, about five nautical miles northeast of the airport. The two pilots, two flight attendants, and 45 passengers aboard the airplane were killed, one person on the ground was killed, and the airplane was destroyed by impact forces and a post-crash fire. Weather conditions at the time of the accident included a wintry mix of icing, snow, fog, and gusty winds.

“The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of this accident was the captain’s inappropriate response to activation of the stick shaker, which led to an aerodynamic stall from which the airplane did not recover.” Numerous contributing factors were also found relating to the actions of the captain and Colgan Air’s management.

In plain language, the crew allowed the airplane to slow to an airspeed below that which was safe under the existing conditions. This triggered activation of an automatic low-speed warning system that shakes the control yoke. The captain’s incorrect reaction to this warning put the aircraft into an out-of-control condition with insufficient altitude for recovery.This tragedy put the spotlight on an insidious problem within the air transportation industry whose root cause can be traced to deregulation.

Prior to the arrival of a free market in the business of providing “passenger seat miles,” competition didn’t exist. Government control of the routes airlines could fly and the price they could charge reduced the passenger’s choice to a matter of brand loyalty based upon relatively superficial factors such as the quality of interaction with gate agents, flight attendants, and to a much lesser degree, the cockpit crew. But in terms of getting from one place to another by air, the overall experience didn’t vary much because of the company name painted on the airplane.

Once the government turned loose of the reins, airlines had to adjust by learning to compete. Suddenly, how well an airline was managed made a difference. A time-sequenced list of bankruptcies, acquisitions, and mergers provides an historical record of the resulting turmoil and serves to punctuate the explosive growth of the industry. Within a relatively short time span, passenger seat miles flown increased exponentially.

There’s a saying that begins with the question, “How do you make a small fortune in aviation?” The answer is, “Invest a large fortune.” And from the perspective of commercial air travel, a key factor is the hard truth that the product of a passenger seat mile on an airliner has no shelf life. When the main cabin door closes for pushback from the gate, the revenue loss from an empty seat can never be recovered, while the cost to fly an airliner from one point to another is fixed. The only way for an airline to generate revenue is to maximize passenger “load factor” beyond that required to break even.

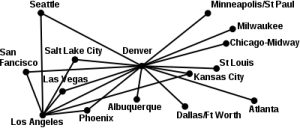

One of the most significant changes in the aftermath of deregulation is the predominance of the “hub and spoke” system and the expansion of regional airline operations. With few exceptions, major air carriers schedule larger airliners for longer flight segments from one major hub city to another.

One of the most significant changes in the aftermath of deregulation is the predominance of the “hub and spoke” system and the expansion of regional airline operations. With few exceptions, major air carriers schedule larger airliners for longer flight segments from one major hub city to another.

To maximize load factors and therefore profits, airlines have to bring passengers into the hub cities to connect them with these longer flights. The only way to accomplish this efficiently is to utlilize smaller airliners to “feed” passengers economically into the major hubs, and that role is filled by operators known as feeder, commuter, or more commonly, regional airlines.

One result of the Colgan Air tragedy is that the airline industry is being forced to address a long-standing problem at the very core of how cockpit crews enter the system system and work their way up the ladder.

As in any union-based profession, seniority rules the life of an airline pilot in terms of cockpit position, equipment flown, home base assignment, schedules, and compensation. You can think of it as a pyramid, with a very large junior-pilot base supporting relatively few senior pilots at the top, best represented by the captain of a heavy jet flying international routes. This pilot gets paid the most, enjoys more time off, and has maximum control over flight schedules to ensure weekends and holidays at home with the discretionary income to enjoy them.

At the bottom of the pyramid resides the regional airline pilot, who makes the least amount of money and flies potentially the most fatiguing schedules. While you may find a rare pilot content with a career flying for a regional carrier, the vast majority serve their time in purgatory only for the opportunity to advance and finally enjoy the good life.

At the bottom of the pyramid resides the regional airline pilot, who makes the least amount of money and flies potentially the most fatiguing schedules. While you may find a rare pilot content with a career flying for a regional carrier, the vast majority serve their time in purgatory only for the opportunity to advance and finally enjoy the good life.

It should come as no surprise that regional airlines understand this better than anyone. They have a “captive” pilot pool because the only practical way for a pilot to gain the minimum flight experience required to apply for a position with the majors is to accept working long hours for little compensation.

All the majors require about the same amount of flight experience to consider an applicant for employment, The regionals require minimum flight experience as well, and traditionally the standards have been quite low. The reality is that with a regional, the total experience level in the cockpit will almost always be much less that that of a major airline.

This is not to imply that regionals have a safety record significantly worse than the majors. They don’t, but the Colgan Air tragedy has highlighted the underlying reality caused by the potential for reduction in safety endemic to a culture of “flying on the cheap.”

Management at a regional airline can easliy be tempted to cut corners to maximize a thin margin for profit. One factor with particularly dangerous potential is if the contract between the major and the regional requires the junior partner to complete a flight in order to be paid for it. As a passenger, it would probably never occur to you that any airline operator might push the limits of safety for purely economic reasons, but it’s naive to ignore the possibility in the harsh economic world of air travel.

In addition, there’s the issue of how the current system integrates regional and major airline flight schedules. Ticketing practices effectively hide the fact that the passenger’s expectation of flying an entire trip with aircraft and crews of a major carrier is often false.

The NTSB this past week held a two-day forum to examine safety issues related to “code-sharing” agreements between major airlines and regional carriers. NTSB Chairman Deborah Hersman says, “We have investigated many accidents in which passengers bought tickets on a major carrier and flew all or part of their trip on a different carrier — one that may have been operating to different safety standards than the carrier that issued the ticket.” According to John Prater, president of the Air Line Pilots Association, “Current regulations never envisioned this model.”

The NTSB this past week held a two-day forum to examine safety issues related to “code-sharing” agreements between major airlines and regional carriers. NTSB Chairman Deborah Hersman says, “We have investigated many accidents in which passengers bought tickets on a major carrier and flew all or part of their trip on a different carrier — one that may have been operating to different safety standards than the carrier that issued the ticket.” According to John Prater, president of the Air Line Pilots Association, “Current regulations never envisioned this model.”

Besides representatives of the NTSB, FAA and the airline industry, presenters at the forum included relatives of crash victims, who provided some of the most dramatic testimony. Some family members said the FAA’s tolerance of different standards for pilots at smaller carriers amounts to a fraud on the public. “Why are the airlines allowed to play that shell game?” asked a father whose daughter died in last year’s Colgan Air crash.

An article in USA Today noted that although six of the nine fatal airline accidents since 2003 involved regional carriers, over longer time periods the safety records are about the same. Airline representatives said the system improves service to hundreds of smaller airports and keeps fares low. Regional airlines account for half of all U.S. passenger flights and about a quarter of all passengers, according to the Washington Post. More details about the forum, including prepared testimony by most of the participants and an archived webcast, are available at the NTSB website.

From the perspective of my experience as an aviator in the military, a major airline, and private corporate aviation, I have long been critical of the way the civilian union-based system abuses pilots at the bottom of the pyramid. That said, I fully understand that the only way to gain flight experience is to spend hours in the cockpit doing what pilots do, and the model that typically pairs a less-experienced first officer with a more-experienced captain is highly effective in transferring core knowledge from one pilot to another.

As the NTSB and the FAA deal with the aftermath of the Colgan Air crash, however, one of the proposed answers is to increase the minimum required flight experience for employment at a regional carrier from the current 250 hours to 1800. That is a knee-jerk response with nothing to recommend it for three reasons.

First, once a young pilot has gained the experience necessary for a commercial pilot rating and can be paid for services rendered, the only practical way to reach the minimum required additional flight hours to apply at a regional carrier is to get a flying job. If working conditions at a regional are poor, this prelude can be far worse because no regulatory oversight exists in terms of limiting the duration of a crew duty day or setting minimum crew rest standards. To increase the time spent in ultra-purgatory by a factor of seven is ludicrous.

First, once a young pilot has gained the experience necessary for a commercial pilot rating and can be paid for services rendered, the only practical way to reach the minimum required additional flight hours to apply at a regional carrier is to get a flying job. If working conditions at a regional are poor, this prelude can be far worse because no regulatory oversight exists in terms of limiting the duration of a crew duty day or setting minimum crew rest standards. To increase the time spent in ultra-purgatory by a factor of seven is ludicrous.

Second, although I don’t know how much more than the current 250-hour minimum would provide a safety enhancement, I do know this: the Colgan Air crash wasn’t definitively a result of the relatively low combined flight hours of the captain and first officer. Far more germane to the accident was the failure of training to prepare them to handle a hazardous situation. And third, the captain on that flight did not have a good record when it came to consistently exhibiting acceptable performance during evaluations.

It doesn’t take much thought to identify the core problems. As industry regulators and watchdogs proceed with addressing the issue of safety within the combined regional and major air carrier operations, hopefully they will put less faith in some arbitrary number of flight hours and focus on the key elements of pilot training, proficiency, and effective evaluation of crew performance.

One Response to Regional Airline Safety Comes Under Fire