After the initial academics-only period, we began a split schedule with classroom instruction in the morning and flying training in the afternoon, or vice versa.

After the initial academics-only period, we began a split schedule with classroom instruction in the morning and flying training in the afternoon, or vice versa.

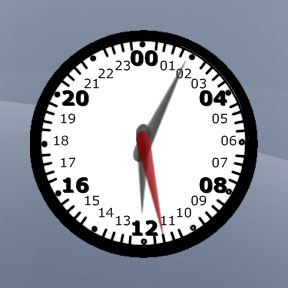

All military time is expressed in a 24-hour clock, so AM and PM had no place in our vocabulary. To enter a classroom for morning academics at “oh-eight-hundred hours” (8:00 am) was fairly civilized, actually. We’d be out of class in time to grab some lunch before reporting to the flight line about 1300 hours (1:00 pm). To complete a training sortie consumed most of the afternoon with the inevitable question-and-answer session with an instructor, flight briefing, suit-up, aircraft preflight, the training flight, and debriefing. After dinner, we’d hit the books to prepare for the next day.

Pilot training was our introduction to a minor (but harsh) reality within military aviation. Most of what we do in terms of training has to be accomplished in daylight hours. Heaven forbid that we should waste any of it. To be ready for takeoff at dawn meant all preflight preparation had to be conducted in a very uncivilized part of the day. It also meant that report times for the weeks of morning schedule flight training required what we referred to as “oh-dark-thirty get-ups.” The last flights on the afternoon schedule landed at dusk, and debriefings usually kept us at the flight line until well after dark.

Transitions from one split schedule to the next were not created equal. Afternoon academics ended at a reasonable hour, as did the next week’s morning academics. But afternoon flying followed by morning flying didn’t leave much time for recharging our batteries. This was especially true if we had to fly on a Saturday, occasionally required when “weather days” grounded the fleet. We’d leave the flight line after dark on Saturday evening and have to be back well before dawn Monday morning.

Transitions from one split schedule to the next were not created equal. Afternoon academics ended at a reasonable hour, as did the next week’s morning academics. But afternoon flying followed by morning flying didn’t leave much time for recharging our batteries. This was especially true if we had to fly on a Saturday, occasionally required when “weather days” grounded the fleet. We’d leave the flight line after dark on Saturday evening and have to be back well before dawn Monday morning.

I have a vivid memory of early mornings during the winter of 1964-65. We would carpool from our quarters to the flight line, and one of my classmates had a brand-new red 1965 Pontiac GTO. He’d start the car about 10 minutes before we needed to leave, turn on the radio and heater (not a very efficient one), and return to his room to finish his morning ritual.

The first three students to arrive at the car had to crawl in the back. For some reason I can’t remember, I usually showed up first and ended up straddling the transmission hump. I’d be sitting there, barely conscious, freezing my you know what off, and more often than not be listening to the #1 international hit of early 1965, “Downtown” sung by Petula Clark. I can still hear it, and it still makes my teeth chatter.

The first three students to arrive at the car had to crawl in the back. For some reason I can’t remember, I usually showed up first and ended up straddling the transmission hump. I’d be sitting there, barely conscious, freezing my you know what off, and more often than not be listening to the #1 international hit of early 1965, “Downtown” sung by Petula Clark. I can still hear it, and it still makes my teeth chatter.

One of the first preflight items is to check the weather. In the mid-60’s at the Reese AFB flight line, that meant looking up at a closed-circuit television mounted to the ceiling. A camera in the weather office was trained on a revolving four-sided tower affair with hand drawn weather maps, observations, and forecasts. It would rotate 90 degrees about every 10 seconds, so we’d have to stand there for half a minute or so to review the data.

We hadn’t been flying for more than a week when a bunch of us were going through the motions of checking the weather because all we’d had to do was look at the sky to know it was going to be a gorgeous day. One of the panels on the display had three capital letters printed on a piece of plexiglass: PNC.

No one said a word until the panel appeared once again. Then from behind me: “What does PNC mean? Did they cover that in class?” No one knew, and that created a common student dilemma: he who asks a question runs the risk of advertising to his classmates that he is the only student who doesn’t know the answer.

Under any other circumstances I wouldn’t have objected. But asking the weather guy anything required using a radio. The question and answer would be broadcast to all the flying squadrons. Not eager to embarrass myself, I replied, “Uh-uh. No way.”

“Oh, come on. Better you than one of us.” Ultimately, they convinced me.

I should have been more cautious and realized the weather guy was going to have fun at my expense. He began with, “I guess you must have been sleeping in class, Lieutenant. It’s a common abbreviation for Purt Near Clear.”

Needless to say, that became a standard way of stating that the weather would not be a factor for the day.

3 Responses to Undergraduate Pilot Training – Split Schedules