One of the major objectives of terror is to elicit a disproportionate response. From that perspective, the attacks of 9/11 succeeded beyond any terrorist’s wildest dreams. A three-pronged assault on the symbols of American dominance in global economics, politics, and military power as an extension of national will have brought us to this. After nine years of continuous warfare and no realistic end in sight, what have we accomplished?

One of the major objectives of terror is to elicit a disproportionate response. From that perspective, the attacks of 9/11 succeeded beyond any terrorist’s wildest dreams. A three-pronged assault on the symbols of American dominance in global economics, politics, and military power as an extension of national will have brought us to this. After nine years of continuous warfare and no realistic end in sight, what have we accomplished?

By any measure, America is domestically better protected from attack. That’s the good news. Reporting the bad takes a bit longer because there’s so much of it.

At the core of our national dilemma lies the unavoidable truth that we can’t afford to pursue what we have defined as indispensable goals: eliminate the ability of terrorism to threaten our way of life and create stable democracies in a region of the world populated by people whose dominant culture and religion are incompatible with the concept.

If we assume that our leaders understand the reality of terror, that no matter how many terrorists we kill there will always be more, then we can conclude that decision-makers recognize the necessity for never-ending vigilance and aggressive counterterrorist strategies. But since we can’t keep American boots on foreign ground indefinitely, we try to establish security by proxy before we bail out.

If we assume that our leaders understand the reality of terror, that no matter how many terrorists we kill there will always be more, then we can conclude that decision-makers recognize the necessity for never-ending vigilance and aggressive counterterrorist strategies. But since we can’t keep American boots on foreign ground indefinitely, we try to establish security by proxy before we bail out.

The fact that we don’t have a very good record in that regard appears to have escaped some folks. And just in case our enemies are wondering, we announce withdrawal dates on the totally illogical assumption that we can predict with any degree of accuracy the outcome of military campaigns and effectiveness of security-force building.

But what if we can, and sometime next year all American troops have been withdrawn from Iraq and Afghanistan? And what if those nations have achieved the stability we envisioned? Then we can implement the proposed cuts in defense spending, right?

Not so fast. Here are quotes (edited for brevity) from a recent article by James Kitfield in the National Journal:

“For an outside-the-box appraisal of the United States’ global role and defense posture and the threats to U.S. interests, Congress asked some of the country’s pre-eminent national security experts to critique the Defense Department’s 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review. In the past, similar ‘red teams’ have proven critical to developing national strategy by testing status quo doctrine, looking beyond the tyranny of the immediate to threats on the far horizon, and above all, confronting conventional wisdom.

“For an outside-the-box appraisal of the United States’ global role and defense posture and the threats to U.S. interests, Congress asked some of the country’s pre-eminent national security experts to critique the Defense Department’s 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review. In the past, similar ‘red teams’ have proven critical to developing national strategy by testing status quo doctrine, looking beyond the tyranny of the immediate to threats on the far horizon, and above all, confronting conventional wisdom.

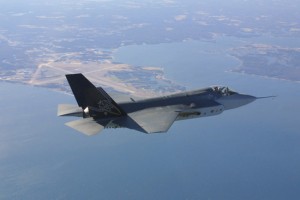

“The QDR Independent Panel, co-chaired by former Defense Secretary William Perry and former National Security adviser Stephen Hadley, didn’t just challenge the narrative of an overburdened superpower indentured to its global commitments; it turned conventional wisdom on its head. In its recently released final report, the panel concluded that the U.S. military force structure is not too big but rather too small. Specifically, it called for a significantly larger fleet of warships and an expanded Air Force with ‘deep strike’ capability primarily to counter the threat posed by a rising China.

“Even though the U.S. has ended combat operations in Iraq and plans to begin withdrawing troops from Afghanistan in 2011, the report calls for maintaining the current level of ground forces to finish those jobs and meet future demands for counterinsurgency, counterterrorism, and stability operations. Rather than cutting new weapons programs, the panel argues for a much more rapid modernization of an aging arsenal.”

To call this a national security strategy disconnect is an understatement in the extreme. Although to narrow focus on a few underlying factors always misses items of importance, consider the following:

Since 2001, America’s annual defense budget has nearly doubled in size. It approaches that of all other nations combined, and in inflation-adjusted dollars is at its highest level since WWII. Think about that for a moment and consider the first sentence of this blog post: One of the major objectives of terror is to elicit a disproportionate response.

Since 2001, America’s annual defense budget has nearly doubled in size. It approaches that of all other nations combined, and in inflation-adjusted dollars is at its highest level since WWII. Think about that for a moment and consider the first sentence of this blog post: One of the major objectives of terror is to elicit a disproportionate response.

If we were to add up the enemy body count and divide that into the cost of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, how much has it cost to eliminate a single terrorist? And today, as we read in the paper about a few terrorists being killed, often by Predator drones carrying state-of-the-art munitions, has anyone compared that to an elephant stepping on an ant?

Our mounting national debt stands at $13 trillion. Not all of that is a result of defense spending, but how hard is it to recognize the relationship between our response to 9/11 and the current fiscal crisis? How hard is it to acknowledge that one attack has helped draw us into a monetary quagmire of catastrophic proportions? How hard is it to understand that while the terrorists will never defeat us militarily, they don’t have to? They’ve lured us into spending ourselves to death.

Loren Thompson, chief operating officer of the Lexington Institute, a defense consulting firm, wrote recently on National Journal‘s website: “We have squandered literally trillions of dollars, directly and indirectly, on combating modest threats exaggerated by our fears, while our economy has declined steadily to a point where it may no longer be able to support our previous superpower status,” At some point, he noted, U.S. political leaders will have to face up to the reality of the country’s economic circumstances and the implied limitations.

“We can’t afford to keep policing a world in which many of our trading partners are growing faster and our military methods are contributing to national bankruptcy. The last thing America needs is a concept of its role in the world that is beyond the capacity of our economy and our political system to sustain, purchased with borrowed dollars that will make the emergence of new ‘peer competitors’ more likely.”

“We can’t afford to keep policing a world in which many of our trading partners are growing faster and our military methods are contributing to national bankruptcy. The last thing America needs is a concept of its role in the world that is beyond the capacity of our economy and our political system to sustain, purchased with borrowed dollars that will make the emergence of new ‘peer competitors’ more likely.”

And now, to protect our well-being and global position, we supposedly need to be spending much more on defense at a time when we desperately need to reduce it. It reminds me of a definition of insanity: to do the same thing over and over again and expect a different result.

Philosopher George Santayana’s quote from 1905 foretells America’s current downward path into history. “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Consider this recent quote from retired Col. W. Patrick Lang, an author and a former senior Defense Department intelligence official, on National Journal’s National Security experts blog:

“In any discussion of harsh geostrategic realities and the U.S. defense posture, the degree to which the United States remains bogged down in Iraq and Afghanistan while China continues its rapid rise looms large. Emerging powers elbowing their way into the established international order have been a fulcrum of conflict throughout history. The rise and inevitable fall of empires has also been a major force in shifting the tectonic plates of the global order, a disruption often preceded by the traditional bane of empire — arrogance and strategic overextension.

“Buried in the current debate is the assumption that the United States is still the world’s hegemon, duty-bound to be prepared to fight everyone, everywhere if imperial interests require it. How can responsible, grown-up people who understand our economic position think that has anything to do with reality?”

From a historical perspective, Lang sees parallels between the United States’ challenges today and the decline of the Roman Empire. “It seems to me that America’s situation today is somewhat like that of the eastern Roman Empire in the time of Justinian: a declining economy; insufficient forces for the mission of re-conquest of Africa and other lost lands; a persistence in pursuing unrealistic goals. All these factors contributed to the long-term decline of the Byzantine state. Let’s not follow that example.”

From a historical perspective, Lang sees parallels between the United States’ challenges today and the decline of the Roman Empire. “It seems to me that America’s situation today is somewhat like that of the eastern Roman Empire in the time of Justinian: a declining economy; insufficient forces for the mission of re-conquest of Africa and other lost lands; a persistence in pursuing unrealistic goals. All these factors contributed to the long-term decline of the Byzantine state. Let’s not follow that example.”

Amen.