If the title of this post is black and/or you see the fighter-pilot header, click on the title to view the featured-image header and continue reading. (Header image credit: sim-outhouse.com)

Almost two years ago, I received this comment from a visitor on my series “Beautiful Aviation Art”:

My watchcap is off to these gallant airmen and their crews, however, once again the crews of the lowly PBY Black Cats are left out of the story. Those men flew into the teeth of the Japanese war machine with a lumbering flying boat painted black as their main defense. They sunk millions of tons of war provisions during the night, then spent the day rescuing downed aviators. They were crucial in early warning at Midway, and other battles. I doubt if the men whose lives were saved by “Dumbo” and the Marines who fought starved-out Japanese soldiers would consider the PBY incidental to the war effort. Let’s give these men and crews their due. –J.L. Reeves, proud son of Lt. Cdr. Columbus DeMerville Reeves II, VPB-33.

Although the delay in doing something about the comment may not indicate it, I couldn’t agree more, and this morning I stumbled upon a post on sofrep.com that I want to share here. It’s a great website based on the acronym SOFREP: [noun] a special operations situation report.

Full credit to the website and author Mike Perry for the post re-published here absent a video clip of a Black Cat returning from a combat mission. See the website to view it. The text and images in Mike’s post follow, including additional images inserted by me with credit noted to other sources.

As a result of the industrial age, machines of war have often garnered as much fame as man himself. In the case of the airplane this proved to be no truer than in the Second World War. Names like Spitfire, Mustang, Flying Fortress and Messerschmitt earned their place in history as legends in their own time.

Then there were the others. Unsung, under-appreciated workhorses that, in some respects, changed the course of battle, single-handedly. But, they always fell victim to the more glamorous looking mounts that shot the enemy from the sky or rained bombs on his cities. Few of their crew ever made the papers, or posed for photographs, instead they plodded on as just another cog in the gears of the armed might humanity, content with their role.

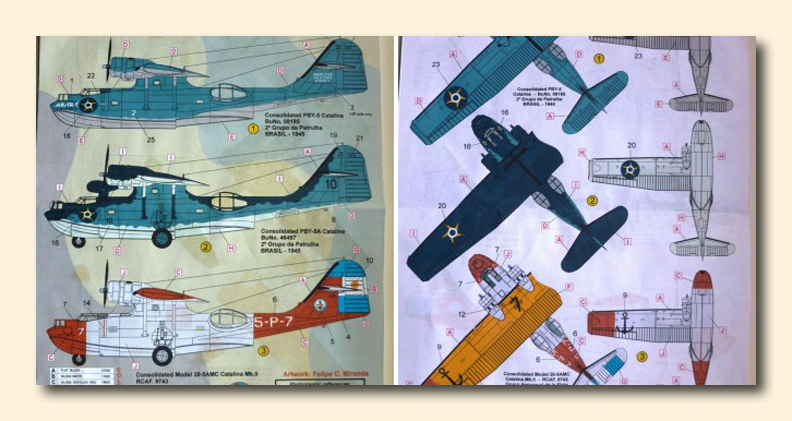

For men who flew the PBY Catalina for the U.S. Navy, this was almost a certainty. An amphibious twin engine patrol aircraft with a boat shaped fuselage and wide squared wings, they spent many a day spanning the far reaches of the world’s oceans, ducking in and out of clouds to find signs of an enemy before anyone else, report him, shadow him, and hope no one, especially a fighter, spotted them.

They had some marvelous successes, though. In 1941, a PBY discovered the feared German battleship Bismarck, which unfolded a chain of events that led to her sinking, and little more than a year later, they found the Japanese fleet approaching Midway, which culminated in turning the tide of the war in the Pacific. Reliable and long ranged, they proved indispensable to commanders who needed timely intelligence.

Yet there were others, a few squadrons, in fact who managed to do things with this aircraft that defied logic. These were the stand outs. They painted it, armed it and sent it off to strike an unsuspecting enemy in the dead of night, often using only the dim lights shining on their instrument gauges to guide them. In the course of their history they built up a formidable reputation and proudly called themselves the “Black Cats.” And in their playground of the Pacific Ocean, they proved more than just a scourge.

Their earliest operations began during the Guadalcanal campaign which started in August 1942. Here the Japanese undertook a massive resupply effort to keep the island from falling, with hopes of retaking it. They sent streams of convoys down the narrow channels of the Solomon island chain and became known as the Tokyo Express. And more often than not, these were run at night, and included warships heading to bombard Guadalcanal’s prize, Henderson airfield.

Since night operations were much too dangerous to involve large numbers of aircraft, a decision was made to use unorthodox methods to harass the Japanese. They came up with the idea of using the PBY, which was found that after some aircraft modification and daring by the crew, might be the perfect answer.

The most visible modification made was its color. From nose to tail every part of the plane was painted matte black. Even the national emblem was darkened (later reversed) to prevent a target for searchlights to focus on. Later on, to keep with the moniker, some sported eyes and whiskers daubed on the nose. For electronics, radars and radio altimeters were installed to ensure navigational safety, and weapons of various types were hung under the wings. Now, with their once clumsy looking ocean blue albatrosses looking more like menacing vultures, the first official Black Cat missions commenced in December flown by crews from Navy squadron VP-12 under Commander Clarence Taff.

Photo Credit: scoopweb.com via Wikipedia Commons

They were an immediate hit. Flying all night, soaring slowly, alone or in small groups above the dark waters they dipped down to ship mast height, to bomb and torpedo Japanese vessels of all shapes and sizes, as searchlights and tracer bullets swept the skies in vain trying to find the lumbering birds unseen, save for the deep chop of their engines.

With their greatest ally, the darkness, stolen from them, the Japanese would watch in horror as a random ship, then another, exploded in a blinding mass of flame and oily smoke that seemed to occur almost every night and at the beckon of those engines.

Not content, Black Cats also worked their magic against islands, terrorizing the enemy as America’s response to “Washing Machine Charlie.” This was a nickname pinned on a lone Japanese night raider who had frequented Henderson field, dropping bombs, hitting nothing but keeping nerves on edge. The Black Cats felt obliged to return the favor, so they visited different airfields dropping bombs of all sizes, as well as beer bottles with razors in the neck to make them scream as they fell. One pilot even dropped hand grenades, door knobs, chains and even shrapnel from an exploded Japanese bomb to rattle the cages of those below.

In missions like these, they would make four successive runs in half-hour intervals over the target before they got rid of everything carried. To say they deprived the enemy of sleep or work when doing this was an understatement.

The Black Cats knew, though, they had little defense should a fighter be nearby, so they developed tactics to keep their vulnerable planes from getting tracked by roaming patrols. The best moves, they found, were low over land and near wave-top level over water. This latter technique was especially effective as it confused an enemy’s depth perception. Since the Cat was nearly invisible against a dark ocean it took an almost suicidal pilot to dive on it unaware of where the Cat’s silhouette ended and the water began.

Once fighting on Guadalcanal ended and moved up the Solomons and inexorably toward Japan, more Black Cat squadrons were added, while VP-12 was withdrawn after having flown over 300 missions.

The new groups continued the Black Cats legacy, plying their deadly trade sinking or damaging thousands of tons of shipping and harassing harbors and employing a new tactic: working hand in hand with PT boats off the coasts as double-edged sword against shipping. This ploy helped them rack up even more nocturnal victories.

And crews were evolving the Catalina itself. Now, more machine guns were being added and even attempts to mount a tank gun were tried, but abandoned because such a beast wouldn’t fit. Nevertheless, this excess of automatic weaponry taught many a night fighter to keep its distance as their porcupine-like target lumbered over the waves at barely 115 miles per hour.

The Cats also made daylight appearances like their blue-attired cousins when reconnaissance was needed or as standbys for search and rescue. It was during one of these that an incredible feat occurred.

During a rescue patrol on February, 14th, 1943, a VP-34 PBY piloted by Lieutenant Nathan Gordon covered a massive daylight raid against Kavieng airfield on an island named New Ireland. Combat had been heavy and planes downed offshore, so he dipped his black bird low looking for rafts or heads bobbing in the waves which seemed heavier than usual.

He eased the Catalina toward the water, but the swells caused it to hit heavy, water spewing through the seams and bilges. He taxied the plane around an empty raft then satisfied there was no one around, lifted off again.

A radio call sent him to another location nearby. Another raft spotted. Men aboard, drifting close to shore.

An enemy boat set out toward it. A bomber strafed its course sending it back to the beach as Gordon set down again, spray erupting around the raft as the Japanese zeroed in on it.

He stopped engines, letting the raft float alongside, as bullets began puncturing the aircraft. Several men were hauled aboard and the Catalina lumbered over the waves.

Just as it lifted off, another call came. More men. Three this time. Again, another hard landing, the Japanese greeting them with bursts of tracer and sea spray kicking up around the plane as the engines stopped and tired hands pulled them inside.

Bouncing into the air, he set course for home. Then it came again. More men sighted. Counting his crew, he realized there were now 19 men aboard with no room left. But it didn’t matter, he was going back.

Gordon thundered low down the beach toward the raft tossing in the waves near shore. The Japanese poured fire at the plane as Gordon slammed it down the black skin bleeding water and oil as he pulled alongside with still engines. The six stuffed themselves aboard as the throttles shoved forward and the wounded, waterlogged, and overloaded cat struggled with each hop of wave, until it rose perhaps by will alone, into the big blue, tracked the entire way by relentless fire. It was to no avail. Gordon had done it, and got them back home a few hours later with his courage and crew bailing water out the hatches.

Word quickly made its way up the chain of command and soon Admiral William Halsey took time from his busy schedule to send the following message: “Please pass my admiration to that saga-writing Kavieng Cat crew. X-ray. Halsey.”

Nathan Gordon received the Medal of Honor.

Photo Credit: sofrep.com

Squadrons stayed active throughout 1943 and into ’44 and included Australian (RAAF) groups. This expanded the operational areas, but the Cat’s days were coming to an end. Better aircraft such as the four-engine maritime B-24 Liberator, the PB4Y, was appearing in greater numbers and exceeding the Catalina’s attributes in most areas. And with their black paint flaking and unplugged bullet holes dotting their forms, the last of the Black Cat squadrons headed back to the U.S. in early 1945 to await the scrapyard. There, the outstanding success and sheer bravery of their crews remained unknown to the worker whose torch began to slice into that scarred and battered aluminum shape that once ruled the night.

U.S. Navy Black Cat Squadrons

- VP-11

- VP-12

- VP-23

- VP-24

- VP-33

- VP-34

- VP-44

- VP-52

- VP-53

- VP-54

- VP-71

- VP-81

- VP-91

- VP-101

PBY Catalina General Characteristics

- Crew: 8 – pilot, co-pilot, bow turret gunner, flight mechanic, radioman, navigator and two waist gunners

- Length: 63 ft 10 7/16 in (19.46 m)

- Wingspan: 104 ft 0 in (31.70 m)

- Height: 21 ft 1 in (6.15 m)

- Wing area: 1,400 ft² (130 m²)

- Empty weight: 20,910 lb (9,485 kg)

- Max. takeoff weight: 35,420 lb (16,066 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × Pratt & Whitney R-1830-92 Twin Wasp radial engines, 1,200 hp (895 kW each) each

- Zero-lift drag coefficient: 0.0309

- Drag area: 43.26 ft² (4.02 m²)

- Aspect ratio: 7.73

PBY Catalina Performance

- Maximum speed: 196 mph (314 km/h)

- Cruise speed: 125 mph (201 km/h)

- Range: 2,520 mi (4,030 km)

- Service ceiling: 15,800 ft (4,000 m)

- Rate of climb: 1,000 ft/min (5.1 m/s)

- Wing loading: 25.3 lb/ft² (123.6 kg/m²)

- Power/mass: 0.034 hp/lb (0.056 kW/kg)

- Lift-to-drag ratio: 11.9

PBY Catalina Armament

- 3× .30 cal (7.62 mm) machine guns (two in nose turret, one in ventral hatch at tail)

- 2× .50 cal (12.7 mm) machine guns (one in each waist blister)

- 4,000 lb (1,814 kg) of bombs or depth charges; torpedo racks were also available

Photo Credit: “Boosher” via mission4today.com

Photo Credit: “Boosher” via mission4today.com

One Response to Black Cats Rule the Night – by Mike Perry