I received the following article from a friend and fellow military pilot and decided to share it on my website because it presents information about an example of air combat in which a much smaller defensive force achieved impressive successes against overwhelming numerical superiority.

Adolf Galland, head of the German Fighter Command during WWII, is (roughtly) quoted as saying, “Only the spirit of attack born in a brave heart can ensure victory in a fighter aircraft no matter how advanced it may be.”

The quote certainly applies to the following example of dedication and bravery in the cockpit combined with brilliant tactical exploitation of enemy weaknesses.

The email I received with the article includes personal comments from two military aviators referring to a period of the air war over Vietnam in which the F-102 “Delta Dagger” (more commonly called the “Deuce”) of the Air Defense Command was sent into combat. As a foreword to the original article, I will only address the key points contained in the emails.

As you will see later in this post, two primary capabilities of a fighter determine how it should be most effectively employed against any given adversary.

First is the combination of thrust and wing loading, which define the ability of the aircraft to accelerate, use the vertical (i.e. climb or descend), and perform what is called the “quickest/tightest turn.” You can think of it as agility in a fight and the ability to get out of one in a hurry if need be.

Second, what kind of air-to-air armamant can the fighter carry? Guns, missiles, a combination of the two? Are the missiles guided by radar or infra-red? Are they contact or proximity fuzed?

Aerodynamically, a delta-wing aircraft like the Deuce has very good turn performance. The bad news is that it will shed airspeed very quickly in a hard turn. Without going into details, the Deuce was a relatively agile airplane in relation to the MiGs flown by the North Vietnamese, but once slowed down, it wasn’t particularly good at disengaging. Combine that with no gun and contact-fuzed missiles designed to engage lumbering bombers, the Deuce began any fight over North Vietnam at a distinct disadvantage. And further, combine that reality with stupidity in the cockpit, and you get the results my aviator friends referred to in the emails.

I’ve edited the following for brevity and to remove the names and a bit of language fighter pilots often use for “emphasis.”

It so happens that the F-102 flight lead who went after a MiG was an arrogant, miserable, glory-seeking idiot and squadron mate of mine before the war. He led his poor wingman to a predictable death. A Deuce may be able to maneuver with a MiG, but not shoot it down with those contact fuze missiles the Deuce carried. Getting near a MiG is a recipe for disaster. The leader’s hunt for glory caused his wingman to die. He should have been court martialed.

I never saw a Mig all the time that I spent over North Vietnam, but there were plenty around us. Our long-range radar guys were calling them out constantly. A couple of Navy A-1s killed a MiG in a head-on attack early in the war, so the bad guys stayed away from us. We could turn around in a phone booth and had 4 20mm [cannon] to point at them. Also, we gave off a poor IR signature so they had to try to gun us.

Having said that, my roomate in Thailand didn’t return from a mission over North Vietman. His flight lead did not see him get shot down and it was thought that he was lost to ground fire. Later, US sources said it was a MiG.

The term “ace” has a number of meanings depending on context. It can refer to a playing card with a single spot on it, ranked as the highest card in its suit in most card games. Informally, it’s a hole-in-one in golf, or a person who excels at a particular sport or other activity, and in tennis and similar games, a service that an opponent is unable to return and thus wins a point.

In military aviation, an ace refers to a pilot who has shot down many enemy aircraft, usually five or more. From WWI through today, the list of aces from many countries includes legendary names that resonate with aviators and non-flyers alike, and except for the Vietnam air war, most could match a particular name with a given conflict.

According to most sources, the final pilot ace totals were two American, one Soviet Union, and sixteen North Vietnamese. Considering the overwhelming superiority of American airpower during the entire conflict, the numbers appear blatantly inaccurate. They aren’t, and the article explains why.

And now the article, subtitled “From the Other Side of the Coin.” (Note: the following text has been edited for brevity and clarity.)

Nguyen Van Coc of the Vietnam People’s Air Force (VPAF) is the top ace of the Vietnam war with 9 kills: 7 aircraft and 2 UAV (Unmanned Airborne Vehicle) “Firebees.” Among those seven US aircraft, six are confirmed by US records, and we should add to this figure a confirmed USAF loss, the F-102A flown by Wallace Wiggins [KIA] on February 3 1968, originally considered a probable by the VPAF. His seven confirmed kills qualified Coc as the top ace of the war, even after omitting the downed UAVs.

Why so many Vietnamese Aces? And why did so many VPAF pilots score higher than their American adversaries? Mainly because of their numbers and tactics.

In 1965, the VPAF had only 36 MiG-17s and a similar number of qualified pilots, which increased to 180 MiGs and 72 pilots by 1968. Those brave six-dozen pilots confronted about 200 F-4 Phantoms of the 8th, 35th and 366th Tactical Fighter Wings (TFWs), about 140 F-105 Thunderchiefs (“Thuds”) of the 355th and 388th TFWs, and about 100 USN aircraft (F-8s, A-4s and F-4s) which operated from carriers on “Yankee Station” in the Gulf of Tonkin, plus scores of other support aircraft (EB-6Bs jamming, HH-53s rescuing downed pilots, Skyraiders covering them, etc.)

Considering such odds, it is clear why some Vietnamese pilots scored more than the Americans. Simply put, they were busier than their US counterparts. And unlike American pilots, who generally finished a tour of duty with 100 combat sorties and rotated home for training, command, or flight test assignments, VPAF pilots flew until they died. (Some US pilots requested and received additional combat tours, but they were the exceptions.)

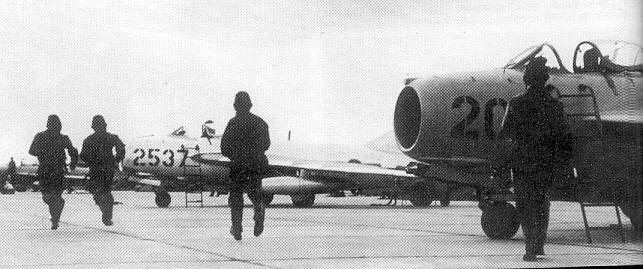

North Vietnamese pilots run towards their MiG-17s to engage US aircraft

North Vietnamese pilots run towards their MiG-17s to engage US aircraft

What about the tactics of both sides? Worried about killing Russian or Chinese advisers, higher headquarters did not allow US air combat forces to attack the North Vietnamese main radar installations and command centers. This provided the North Vietnamese with a significant tactical advantage because VPAF pilots flew their interceptors with superb guidance from ground controllers, who routinely positioned the MiGs in perfect ambush battle stations.

The MIGs made fast and devastating attacks against US formations from several directions. Slower MiG-17s performed head-on attacks and the faster MiG-21s attacked from the rear. After shooting down a few American planes and forcing some of the F-105s to drop their bombs prematurely, the MiGs did not wait for retaliation. They disengaged rapidly, and this guerrilla air warfare proved very successful.

Such tactics were augmented by less-than-effective American practices. Day after day in late 1966, for example, F-105 formations launched at the same times, used the same call signs, and flew the same flight paths to and from their targets. The North Vietnamese took advantage of this predictability in many ways, culminating in December, 1966, when MiG-21 pilots of the 921st Fighter Regiment (FR) intercepted the F-105s before they were joined by their F-4 escorts, downing 14 F-105s without suffering any losses.

Retaliation turned the tables on the North Vietnamese on January 2, 1967, when Col. Robin Olds executed Operation “Bolo,” in which F-4s mimiced the F-105 strike force and lured the MiGs into a trap with teeth.

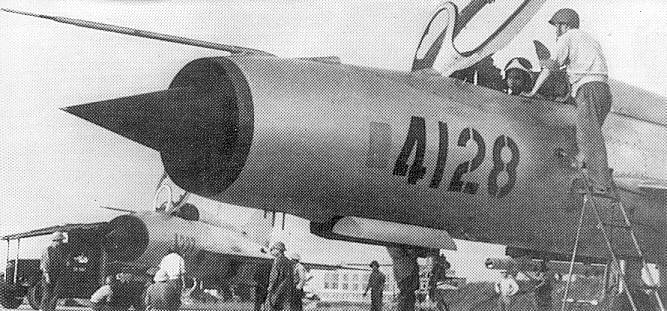

North Vietnamese ground crews prepare 2 MiG-21’s for air combat

North Vietnamese ground crews prepare 2 MiG-21’s for air combat

What about training? In the mid-1960s, American pilots were focused on the use of air-to-air missiles like the radar-homing AIM-7 Sparrow and infra-red guided AIM-9 Sidewinder. They had forgotten, however, that a skillful pilot in the cockpit was as important as the weapons he uses.

[Note: With due respect to the original author of this article, this is not an accurate representation of why air-to-air missiles had become the primary weapon for air combat. As is so often the case, the powers that be sitting behind desks had made the erroneous conclusion that in the modern age of jet fighters, the gun had been rendered obsolete. From personal experience in the cockpit at the time, I can attest to the fact that pilots at the pointy end of the sword did not agree with that assessment.

I wish I’d said this, but I have to give credit to a fellow fighter pilot, who likened a dogfight between an F-4 armed only with missiles and a MiG with machine guns and a cannon to a knife fight in a phone booth between an adversary carrying a sabre and the other with a dagger. We fought that battle over tactics for years and finally won, but not until late in the air war in Vietnam.]

The VPAF knew that, and trained its pilots to exploit the superb agility of the MiG-17, MiG-19 and MiG-21 by getting into close combat, where the heavy Phantoms and Thuds were at a disadvantage. Only in 1972, when the “Top Gun” program improved the skills in aerial combat of USN Phantom pilots and the USAF F-4E appeared with a 20 MM built-in Vulcan cannon, could the Americans neutralize that North Vietnamese edge.

A final comparison to explain the number of VPAF aces compared to those of the US may seem contradictory, but the overwhelming numerical superiority of US air combat forces meant that from the point of view of the North Vietnamese pilots, the aerial battlefield was a “target rich environment.” American airmen, however, could not find enough enemy aircraft to pile up large scores simply because there weren’t that many MiGs around. The VPAF never had more than 200 combat aircraft, only a fraction of which would be airborne at any one time.

These factors created more Vietnamese aces than American and provided opportunities for a few of those to pile up bigger scores than their American counterparts. Officially, of the 16 VPAF Aces during Vietnam War, 13 were MiG-21 pilots, and three were MiG-17 drivers.

VPAF Aces Nguyen Van Bay ( 7 kills ) and Nguyen Van Coc ( 9 )

VPAF Aces Nguyen Van Bay ( 7 kills ) and Nguyen Van Coc ( 9 )

Here are some accounts of deeds performed by those valiant pilots who faced the most powerful air force in the world in defense of their homeland, and who earned the respect of their enemies, the American airmen.

Col Toon: Readers familiar with American military aviation may have heard of the legendary North Vietnamese ace, Col. Toon (or Col. Tomb). Why is he not listed here?

Because he was precisely that: legendary. No Colonel Toon ever flew for the VPAF. He was a figment of the American fighter pilots’ imagination and ready-room chatter. “Col. Toon” also may have been shorthand for any good Vietnamese pilot, like the solo nighttime nuisance bomber in WWII called “Washing Machine Charlie.”

Nguyen Van Bay: When the 923rd FR was created on September 7, 1965, Nguyen Van Bay was one of the students chosen to fly the MiG-17F Frescos. His training ended in January, 1966, and soon the young Lt. Bay saw action against American aircraft.

On June 21, 1966, four MiG-17s of the 923rd FR engaged an RF-8A recce plane and its escorting F-8 Crusaders of VF-211. Even as the escorting Crusaders destroyed two MiGs, Nguyen Van Bay opened his score when he shot down the F-8E flown by Cole Black, who ejected and became a POW. Even more important, the VPAF pilots achieved their main goal. As Bay and his buddies distracted the escort, Phan Thanh Trung in the lead MiG shot down the RF-8A. The pilot, Leonard Eastman, was also taken prisoner.

A week later on June 29, Bay and three more MiG-17 pilots engaged American F-105Ds heading for the fuel depots in Hanoi, North Vietnam. Together with Phan Van Tuc, Bay surprised and shot down a Thud. His victim, the leader of the US formation, turned out to be Major James H. Kasler, a Sabre Ace during the Korean War with 6 MiG kills.

Bay’s greatest feat happened on April 24, 1967. Now a flight leader, he scrambled from Kien An airfield and led his flight of MiG-17Fs against a USN raid on the Haiphong docks. Bay closed on an unaware F-8C of VF-24 and broke it into pieces with a burst of deadly 37mm shells.

The F-8C, piloted by Lt. Cdr. E.J.Tucker, caught fire and crashed. Tucker ejected, was captured, and died in captivity. The escorting F-4Bs of VF-114 entered the battle and fired several Sidewinders at Bay, but his wingman, Nguyen The Hon, radioed a warning. Bay successfully evaded all the missiles, turned his MiG-17 towards one of the Phantoms and shot it down with cannon fire. Lt. Cdr. C.E. Southwick and Ens. J.W. Land ejected safely and were rescued.

The next day, April 25, Bay’s flight of MiG-17s scored again, shooting down two A-4s with no losses. Both kills were confirmed by the US Navy: Lt. C.D. Stackhouse became a POW and Lt JG A.R. Crebo was rescued.

Bay was awarded the Hero’s Medal of the Vietnamese People’s Army for his outstanding skill and bravery in combat and for his superb flight leadership.

In early 1972, this Vietnamese MiG ace and his buddy Le Xuan Di were trained by a Cuban advisor in anti-ship warfare. On April 19, 1972, they attacked the destroyers USS Oklahoma City and Highbee,which were shelling targets in Vinh City. While Bay caused only slight damage to the Oklahoma City, Le Xuan Di hit one of the Highbee’s stern turrets with a 500 pound bomb. It was the first air strike suffered by the USN 7th Fleet since the end of WWII.

Nguyen Doc Soat: One of the merits of the Vietnamese People’s Air Force was that the more successful pilots could transfer their combat experience to novice students. Assigned to the 921st FR as a MiG-21 pilot, Soat’s instructors were the hottest VPAF pilots in the outfit: Pham Thanh Ngan (8 kills) and the top Vietnamese ace, Nguyen Van Coc (9 victories). Soat couldn’t ask for better teachers. While he did not score kills at that time, he gained valuable experience.

Reassigned to the recently created 927th FR when Operation “Linebacker I” began in May, 1972, Soat was ready to show his abilities. On May 23rd he scored his first victory, downing a USN A-7B Corsair II with 30mm fire. His victim was Charles Barnett (KIA).

On June 24, 1972 two MiG-21s flown by Nguyen Duc Nhu and Ha Vinh Thanh took off from Noi Bai to intercept F-4 Phantoms attacking a factory in Thai Nguyen, North Vietnam. The American fighter escort reacted rapidly and headed towards them.

But those MiGs were only bait. Suddenly two MiG-21s of the 927th FR appeared, piloted by Soat in the lead aircraft and his wingman, Ngo Duy Thu. The MiGs took the escorting F-4Es by surprise. Soat downed the F-4E of Pilot David Grant and Weapons System Operator William Beekman with a heat-seeking R-3S Atoll missile. Both crewmen became POWs. Thu also caused the ejection of another Phantom crew. [Note: The original article gave no details and I haven’t been able to determine how Thu did that.]

Nguyen Doc Soat scored some of his F-4 Phantom kills while flying the MiG-21

Nguyen Doc Soat scored some of his F-4 Phantom kills while flying the MiG-21

Three days later, Soat and Thu scrambled from Noi Bai and headed towards a flight of four F-4s. But they knew that eight more Phantoms were incoming, so they did not risk being sandwiched by the arriving US fighters. They turned back, climbed to 15,000 feet and waited.

Their patience was rewarded as they surprised the trailing pair of F-4s. Both Soat and Thu bagged one F-4E each with R-3 missiles. The crew of Soat’s victim was captured.

On August 26, 1972, Soat claimed the only USMC Phantom downed in air combat during the Vietnam War. The F-4J Radar Intercept Officer was rescued, but the pilot was killed. Soat scored his last victory on October 12, when he destroyed the F-4E crewed by Myron Young and Cecil Brunson. Both men were captured.

Along with Nguyen Van Coc and other VPAF vets, Soat is a living legend in the country for which he bravely and skillfully fought so many years ago.

Source: S. Sherman and Diego Fernando Zampini [abridged]

Other Sources:

- Air War Over Vietnam, Dr. Itsvan Toperczer, Squadron/Signal Publications Inc., 1998

- MiG-21 Units of the Vietnam War, Istvan Toperczer, 2001, Osprey Military

- MiG-17/19 Units of the Vietnam War, Istvan Toperczer, 2001, Osprey Military