If you have visited this logbook in the past, you may know that my original intent for it has changed. The idea was to attract visitors with stories to tell about their experiences in aviation either as a passenger, a pilot, or both. A few of my friends offered content to help me get the logbook up and running, but it quickly became apparent that the number and type of visitors to my site couldn’t support the concept.

To deal with that reality, I decided to use the term “visitor” a bit loosely and post stories of interest that had been published elsewhere. They’re like passersby who have been shanghaied off the street by an aggressive merchant, if you will. That’s me, armed with one of those stage hooks.

To deal with that reality, I decided to use the term “visitor” a bit loosely and post stories of interest that had been published elsewhere. They’re like passersby who have been shanghaied off the street by an aggressive merchant, if you will. That’s me, armed with one of those stage hooks.

The following story has made the rounds more than once, but it’s worth whatever added exposure I can provide. Please take a moment to read it, and the next time you chance upon someone who appears to be one of the greatest generation, take the opportunity to shake hands with the last of the breed. It won’t be long before you’ll never get another chance.

And now, the harrowing story of the “All American”:

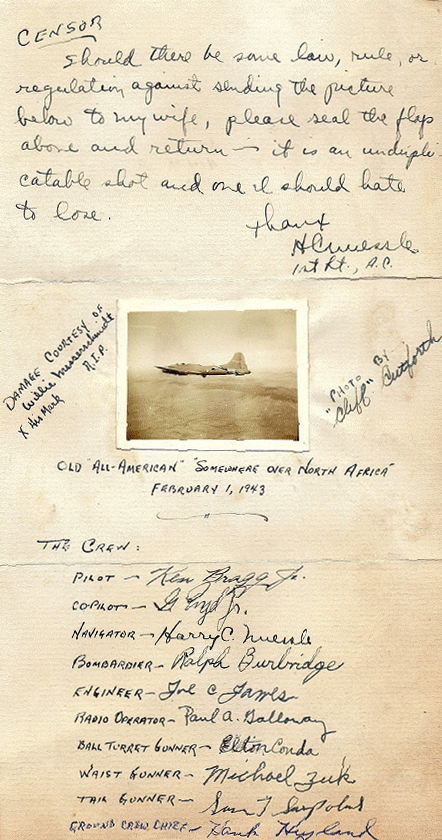

B-17 “All American” (414th Squadron, 97BG) Crew

- Pilot- Ken Bragg Jr.

- Copilot- G. Boyd Jr.

- Navigator- Harry C. Nuessle

- Bombardier- Ralph Burbridge

- Engineer- Joe C. James

- Radio Operator- Paul A. Galloway

- Ball Turret Gunner- Elton Conda

- Waist Gunner- Michael Zuk

- Tail Gunner- Sam T. Sarpolus

- Ground Crew Chief- Hank Hyland

A mid-air collision on February 1, 1943, between a B-17 and a German fighter over the Tunis dock area became the subject of one of the most famous photographs of World War II.

An enemy fighter attacking a 97th Bomb Group formation went out of control, probably with a wounded pilot, then continued its crashing descent into the rear of the fuselage of a Fortress named All American, piloted by Lt. Kendrick R. Bragg, of the 414th Bomb Squadron.

When it struck, the fighter broke apart, but left some pieces in the B-17. The left horizontal stabilizer of the Fortress and left elevator were completely torn away. The two right engines were out and one on the left had a serious oil pump leak. The vertical fin and the rudder had been damaged, the fuselage had been cut almost completely through, connected only at two small parts of the frame. The radios, electrical and oxygen systems were damaged. There was also a hole in the top that was over 16 feet long and 4 feet wide at its widest, and the split in the fuselage went all the way to the top gunner’s turret.

Although the tail actually bounced and swayed in the wind and twisted when the plane turned and all the control cables were severed except for a single elevator cable, the aircraft still flew. The tail gunner was trapped because there was no floor connecting the tail to the rest of the plane. The waist and tail gunners used parts of the German fighter and their own parachute harnesses in an attempt to keep the tail from ripping off and the two sides of the fuselage from splitting apart. While the crew was trying to keep the bomber from coming apart, the pilot continued on his bomb run and released his bombs over the target.

When the bomb bay doors were opened, the wind turbulence was so great that it blew one of the waist gunners into the broken tail section. It took several minutes and four crew members to pass him ropes from parachutes and haul him back into the forward part of the plane. When they tried to do the same for the tail gunner, the tail began flapping so hard that it began to break off. The weight of the gunner was adding some stability to the tail section, so he went back to his crew position.

The turn back toward England had to be very slow to keep the tail from twisting off. They covered almost 70 miles to make the turn home. The bomber was so badly damaged that it was losing altitude and speed and was soon alone in the sky. For a brief time, two more Me-109 German fighters attacked the All American. Despite the extensive damage, all of the machine gunners were able to respond to these attacks and soon drove off the fighters. The two waist gunners stood up with their heads sticking out through the hole in the top of the fuselage to aim and fire their machine guns. The tail gunner had to shoot in short bursts because the recoil was actually causing the plane to turn.

Allied P-51 fighters intercepted the All American as it crossed over the Channel and took one of the pictures shown. They also radioed to the base, describing that the empennage was waving like a fish’s tail, the plane would not make it, and to send out boats to rescue the crew when they bailed out. The fighters stayed with the Fortress, taking hand signals from Lt. Bragg and relaying them to the base. Lt. Bragg signaled that 5 parachutes and the spare had been “used” so five of the crew could not bail out. He made the decision that if they could not bail out safely, then he would stay with the plane and land it.

Two and a half hours after being hit, the aircraft made its final turn to line up with the runway, still over 40 miles away. The aircraft commander carefully guided the crippled bomber to an emergency landing and a normal roll-out on its landing gear.

When the ambulance pulled alongside, it was waved off because not a single member of the crew had been injured. No one could believe that the aircraft could still fly in such a condition. The Fortress sat placidly until the crew exited through the door in the fuselage and the tail gunner had climbed down a ladder. A that moment, the entire rear section of the aircraft collapsed onto the ground. The rugged old bird had done its job.