I’ve never met Wayne Blickenstaff. I know of him through my good friend and fellow writer John Jones, who told me about Wayne’s background as a WWII fighter pilot. John lent me a copy of a book written by Marvin Bledsoe, one of Wayne’s squadron members, titled Thunderbolt: Memoirs of a World War II Fighter Pilot.

Wayne figures prominently in Bledsoe’s account, and I became personally interested in the story of his combat experience as well. John told me that Wayne had also written a book but never published it, and I knew that it contained enough tales to fill this Visitor Stories Logbook many times over.

I also knew that Wayne considers what he and other members of “the greatest generation” did in the defense of freedom as nothing particularly special. I take great exception to that, and from my own little piece of the online universe, I will pay tribute and homage to the boundless courage, dedication, and sacrifice of men like Wayne Blickenstaff.

My first attempt, titled “A Fighter Pilot’s Office” included the following painting of Wayne’s P-51 D Betty-E:

At the end of this post, you will find another painting of Wayne’s P-51. When I first saw it, I asked John if he thought Wayne would object to me posting it on my blog and whether I could share with readers some particulars about his time in combat. The next thing I knew, Wayne contacted me and graciously offered the following account of an incredibly intense few moments spent in a fighter pilot’s “office.”

The very slightly edited text of Wayne’s story follows:

Thank you for all those great words, Tosh, but I am only one of many who happened to be the right age at the right time to be involved in that war. I was out of art school for a year and just beginning to find my way. On that Sunday when Pearl was bombed, I knew I had to go, so I enlisted, as did almost everyone I knew.

John has a copy of my book, which documents all of those questions you ask, as well as the missions. If you want to use any of that stuff on your site it’s okay with me. There are a lot of missions, and I just looked again at the one I wrote about the five destroyed, and it’s probably the most exciting from a fighter pilot’s viewpoint, so I thought I’d tack it on to this e-mail. I finished with 133 missions and 457 combat hours. Here’s the story of that mission . . .

In March, 1945, the 353rd flew 23 missions in 21 days, making it the busiest month since October. The Luftwaffe was in the air again and the group made contact with them on six of our missions, destroying 60 airplanes.

Losses, however, were the highest in group history. Twenty planes were lost and 11 damaged. Of those lost, one pilot bailed out safely over England when his plane iced up, three were known killed and the rest were MIA, about half surviving as POW’s.

The start of the last great offensive action to end the war started in the latter part of the month as General Patton bridged the Rhine River and made his way toward Frankfurt, Germany, in conjunction with the Allied Airborne Army. In a massive and critical operation, Patton’s troops crossed the Rhine River and headed for Frankfurt with the Allies dropping supplies and reinforcements. For want of a better label, someone dubbed it R Day — and it stuck.

Our job was to fan out ahead as air support for both the troops and the Ninth Air Force, which was giving the close ground support needed.

March 24, 1945:

Ben Rimmerman (Col. Group C.O.) took “A” group out at 8:00 AM. The 350th (my squadron) came back early and we formed “B” group, flying 5 flights and one from the 352nd, and I took them out again at 1:00 PM. Ben brought his group back, reformed, and went out again at 2:30.

We were about 15,000 feet, heading for Zwolle, our assigned area. About 2:30, our controller, Nuthouse, directed us to patrol the Rhine-Dummer Lake area. My adrenaline started to flow and I turned left.

“Seldom (our code) Leader here,” I said. “Stay alert now. We may have something.” I was remembering that other day — now past history — when Nuthouse had vectored us into our biggest scoring day.

“Nuthouse to Seldom Leader.”

“Roger, Nuthouse. Go ahead.”

“Return to assigned area.”

“Roger, Nuthouse.” My adrenaline took a nose dive. Now what? False alarm?

I swung around to 150 degrees, heading south again toward the Hersfeld-Kassel area and dropped down to about 7000 feet. We swept the whole area uneventfully, then turned north again toward Kassel.

Bingo! Just west of Kassel I spotted about 15 FW-190’s, low about 3000 feet and heading west toward the front lines. They were carrying bombs. I was so excited I didn’t see the group of ME-109’s flying top cover until Lee, my element leader, pointed them out.

(Note: The image of the FW-190 above is of a restored airplane, and the insignia do not accurately depict those used during the war.)

(Note: The image of the FW-190 above is of a restored airplane, and the insignia do not accurately depict those used during the war.)

I dumped the stick forward and went into a right diving turn. We needed a positive identification. “Seldom here — I’m going down after them. Blue flight, take the top cover. Red, stick with me.”

“Roger, Seldom. Blue here.”

Both groups of enemy fighters were flying in a line-abreast formation and obviously hadn’t seen us yet. I pulled up behind and to the right of the outside aircraft and found myself staring at the big cross painted on the side of the fuselage. I slipped in behind and opened fire as Red flight barged right into the center of the formation.

All hell broke loose!

Just as I pulled the trigger the German pilot saw me, jettisoned his bomb, and made a hard right turn up. Thanks to the G-suit I managed to stay with him, pulling 6 or 7 G’s for about 180 degrees, getting strikes all over the wings and fuselage. He rolled completely over and dove straight into the trees, disintegrating into a puffy ball of smoke.

The rest of my flight had each picked a plane before the Germans broke. Hartley and Lee (White 2 and 3) chased their planes into the ground. I lost track of White 4.

Red 1 was bounced by the 109’s from above before he got a chance to shoot — the 109’s were vigilant!

I glanced around. It was less than a minute since I had begun firing and what I saw was incredible. I was looking at a great whirling dog fight, right on the treetops — black smoke exploding out of the trees occasionally. I thought of those instructors back in the States that told us the days of the old World War I dogfights were over!

Into this mess of P-51’s, 190’s and 109’s, came Yellow and Green Flights, adding eight more planes to the confusion. I saw one of our planes (later identified as May, Red 4) shoot down a 109 that had bounced Prescott, his element leader. At the same time there were four 109’s lined up behind him. It all happened so fast no one could get to him. He knew they were there and broke violently to the left, ramming right into one of the 190’s and tearing his left wing off. He was barely high enough, but managed to bail out. Someone reported later seeing a downed 109 on the ground with a wing embedded in its cockpit.

We were all so close to the ground and there were so many airplanes going in so many different directions it was difficult to see anything that made sense. I needed to be higher. I yanked the stick back — and looked right down the nose of a 190, wings all lit up with flashes. It hardly even registered that he was firing and that we missed head-on contact by inches. I leveled off about 5000 feet.

By now I had the vivid impression of a disturbed wasps’ nest with streaks of fire arcing toward the ground and great exploding fireballs and black smoke pouring out of the trees.

There was a lone 109 below me heading off to the left. I rolled and dove toward him but he saw me and broke to the right. I continued with the roll and started my firing with the trees overhead. My speed was so much faster than his I almost rammed into his rear end, but the plane started to break up before I got there and fortunately I managed to dodge the pieces. His canopy came off and he was half out when the plane slammed into the ground in a burst of fire.

I climbed back up thinking it must be about time to reform the group. How wrong could I be? There was no sign of a let up in the action.

“Seldom Leader break right!”

I did! There was a 109 coming down at me from about 4 o’clock! Thank you, whoever you are. I saw no one but the 109.

(ME-109: Illustration by aviation artist Ed Markham)

(ME-109: Illustration by aviation artist Ed Markham)

I had yanked the stick back and jammed full right rudder into a tight turn, catching the 109 by surprise and winding up in a dive right on his tail. I fired and smoke came pouring out of his plane. He rolled over and went straight into the trees. I found myself in a perfect position as I pulled up and snapped a picture, just as the plane exploded, with the K-25 camera mounted in my cockpit.

My speed again took me up.

“Blue Leader here — I need some help! I’m on the treetops going around with a couple of 190’s!”

Elder! I looked down and saw a 190 and a P-51 going around in a circle. The P-51 was firing, but I could see tracers which meant only 50 more rounds in each gun. There were two more 190’s on his tail and two others circling above.

“I see you Blue Leader, This is seldom. I’ll be right there.”

“Blue 3 here — me too.”

I rolled over and went down to latch onto the first plane on his tail. I pulled the trigger and watched as only one gun fired. Damn! What now? Jesus — I hit him! What luck! Smoke poured out of his engine and he split-essed into the ground.

Strikes on my wings! Christ! — the other 190’s! Basic mistake — too engrossed in what I was doing to look around! I yanked the stick back and got the hell out. I glanced back to see a P-51 firing at the plane behind me. Guthrie — Blue 3. The other two 190’s were nowhere in sight.

I went up again, thinking once more about reforming, but saw a 190 circling about 1000 feet below.

“This is Seldom,” I said. “I have a 190 cornered but I need someone with some ammunition left,”

“Where are you Seldom?”

“High at 6000 feet.”

“I don’t see you. Hang onto him — I’ll keep looking.”

Great! If I don’t do something soon I’ll lose him. Obviously everyone’s pretty busy with their own thing. Well, to hell with it! I’ll go after him with my one gun . . .

The German pilot had not noticed me yet. I dove down, coming in on his tail from below, hoping he couldn’t see me. Have to make this one good or I’m in trouble. I waited as long as I could — took careful aim — and pulled the trigger. The tracers putt-putted out from the one barrel, looking puny and inadequate, but there were strikes and the plane started to smoke. Good God! I actually hit him! The plane slid off to the left and crashed into the ground.

The fifth for the day!

All of a sudden it fell quiet. Something had changed. I looked around and could see only Mustangs milling about. Again — The impression of a peaceful sunny landscape marred only by 20 or 25 fires scattered throughout the acres of green below.

“Seldom Leader here,” I said. “Let’s go home.”

At the debriefing we tallied up the score. We lost five planes but destroyed 29, making the 353rd’s greatest single day’s air victory of the war. Major Elder also shot down five, which also broke a record for the Eighth Air Force — the only time two pilots of the same group got five apiece in one engagement.

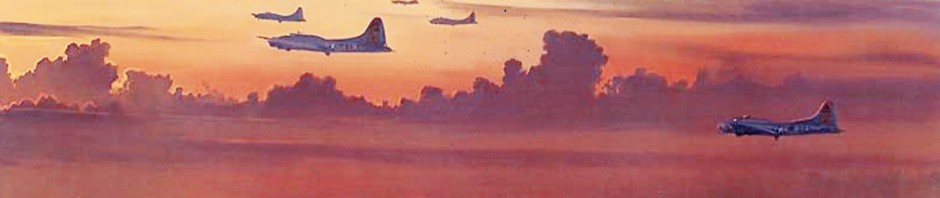

Note from Tosh: I have partially completed a series in the Single Ship Logbook titled “Beautiful Aviation Art” that honors both WWII aviators and the artists who depict specific wartime events with a skill that I can barely comprehend. As an addendum to Wayne’s story, I have inserted an image of a painting that is not part of my original source material for the art series, but could stand its ground in any collection, anywhere, anytime. Here are the details, followed by the image:

- “The Long Ride Home” by William Phillips

- Signed Limited Anniversary Edition Giclee on Canvas, Unframed

- Image Size: 31 X 21 in.

- Edition Size: Not to Exceed 150

- Available here

Text accompanying the painting on the website gallery: By late-1944, the Allies controlled the skies over the newly liberated countries of Western Europe. But when the bombers of the mighty Eighth Air Force ventured into the heart of Nazi Germany, few missions proceeded without their fighter escorts close at hand. Now, for only a short time, the classic William S. Phillips homage to the bond between the Flying Fortresses and their “Little Friends” is available as a Greenwich Workshop Anniversary Edition.

The Long Ride Home features the P51-D Mustang Betty-E piloted by Lieutenant Colonel Wayne Blickenstaff of the 350th Fighter Squadron/353rd Fighter Group. “Ramrod” was the code word that designated these escort missions. Blickenstaff became a double ace during the war, incredibly shooting down five of those ten enemy aircraft in a single mission to become an Ace in a day.

By the war’s end, Blickenstaff would receive the Distinguished Service Cross, the Silver Star, the Distinguished Flying Cross with three oak leaf clusters and the Air Medal with seven oak leaf clusters. The 353rd would be credited with destroying 330.5 enemy aircraft in the air and another 414 on the ground. These were the “Little Friends” you wanted around when the going got tough.

A raid into Germany meant a long day and a long mission. It was a grueling, intense and deadly endeavor that was not without its moments of serenity, beauty and a comradeship known only to men at war. The men are tired, and some in this armada may be wounded. Soon, with what little light there is left in the day, the groups will separate and return to their bases for debriefing and rest following The Long Ride Home.

5 Responses to The Day of the Ace – by Wayne Blickenstaff – and The Long Ride Home