In the previous Writer’s Desk logbook entry titled “The Bungalow Analogy,” I noted my intention to follow up with a personal concept linking the initial creative process of writing a novel with the editing necessary during subsequent revisions. My objective here is to suggest that ignoring (or being unaware of) the structural elements of modern fiction risks creating a shaky foundation and a less-than-sound story.

As mentioned elsewhere in the Writer’s Desk logbook, the terminology used by writers when discussing their craft is often a source of less-than-effective communication. Unlike scientific terms that convey the same meaning no matter which scientist uses them, writers bring to the table a unique vocabulary filled with imprecise semantics. I dealt with a prime example (point-of-view) in a series of posts titled “Grenade in the Room.” An alternate title might be, “How to Create Chaos at Roundtable.”

As mentioned elsewhere in the Writer’s Desk logbook, the terminology used by writers when discussing their craft is often a source of less-than-effective communication. Unlike scientific terms that convey the same meaning no matter which scientist uses them, writers bring to the table a unique vocabulary filled with imprecise semantics. I dealt with a prime example (point-of-view) in a series of posts titled “Grenade in the Room.” An alternate title might be, “How to Create Chaos at Roundtable.”

Another common source of unfulfilling discussion is the word premise. Some years ago, the “icebreaker” question to begin our meetings asked each member of the group to define it. With twenty writers in attendance there may not have been that many definitions, but almost. Discussions about the importance of writing a premise also display a similar range of opinion, from “none,” to “never start a novel without one,” to “finish the novel first and then come up with a premise that fits.”

This post isn’t about premise per se, but it’s important for my purposes here because it emphasizes my belief that good stories ride on the backs of main characters. That’s where an effective premise most often begins, and if we call this the cornerstone of structure, then in my opinion we build upon premise with scenes, the essential building blocks of fiction.

This post isn’t about premise per se, but it’s important for my purposes here because it emphasizes my belief that good stories ride on the backs of main characters. That’s where an effective premise most often begins, and if we call this the cornerstone of structure, then in my opinion we build upon premise with scenes, the essential building blocks of fiction.

Two of my favorite how-to books are Scene & Structure by Jack Bickham and Theme & Strategy by Ronald Tobias. Drawing from these two for the purposes of this post, I submit that a writer’s story strategy and scene selection are core elements of fiction that works. As mentioned in the previously referenced post, while some writers may be able to create structurally sound stories by simply letting the words flow onto the page without outlines or planning of any kind, I believe the vast majority of our efforts benefit from some degree of analysis, if not before, then certainly after the fact.

To illustrate the point, I offer my concept of “text time,” a term which combines not only the amount of text under consideration, but the time it takes a reader to read it. A page of dialogue, for example, with a typical back-and-forth participation between two characters, has lots of white space and can be read more quickly than a page of long narrative paragraphs.

In order to assess the impact of a writer’s strategy on how the story presents itself on the page, an analysis of the amount of text time devoted to each of the major structural elements of fiction can provide an instructive view of proportion. To create a visual presentation of the relative contribution of each, one only needs to assign a different highlight color to each element.

In order to assess the impact of a writer’s strategy on how the story presents itself on the page, an analysis of the amount of text time devoted to each of the major structural elements of fiction can provide an instructive view of proportion. To create a visual presentation of the relative contribution of each, one only needs to assign a different highlight color to each element.

For use within a group environment, this first requires agreement with regard to the structural elements under consideration and the terminology used to define them. In the interests of avoiding problems with semantics, I offer the following:

Dialogue: a conversation between two or more people. This one is easy to identify on the page because almost anything in quotes qualifies.

Narrative: a spoken or written account of connected events; a story; the narrated part or parts of a literary work as distinct from dialogue. This one is not so easy, because narrative contains sub-parts that serve specific purposes in fiction, and to lump them together fails to recognize the discrete impact of each function on the story. This means that some narrative will be highlighted differently to indicate its specific contribution.

Backstory: a history or background created for a fictional character. I submit that this term can be divided into two parts, which more clearly differentiates between their unique functions.

Background: the circumstance, facts, or events that influence, cause, or explain something. As distinct from past events that relate to individual characters, my use of the term “background” applies to a group of characters, such as a tragic weather event (like the killer tornadoes currently in the news) that almost wipes out a town. How that common event affects each character differently and alters individual lives then becomes backstory.

Exposition: a comprehensive description and explanation of an idea or theory. This structural element is crucial for developing the reader’s understanding of something that cannot be considered common knowledge. A trip in an automobile set in current day needs no text time devoted to how the vehicle works, how it’s driven, what the highways are like, etc. Tell this story in the 1920s, and the writer needs to know a lot about these subjects and correctly insert them into the story. Not as authorial intrusions in the form of an info dump, but organically within the story so the details flow outward from current story time rather than being layered on top because the author decides that’s the place they need to be.

Scene: a sequence of continuous action in a play, movie, opera, or book. In fiction, this means moment-by-moment, with dialogue and stage direction, told as it happens in current story time. Good scenes have a beginning, middle, and end. They include one or more characters’ goals driven by unique motivations that create choices, conflict and tension, and involve significant consequences of failure.

Sequel: something that takes place after or as the result of an earlier event. In fiction, this term takes on a specific (ala Bickham) meaning to include the normal reaction sequence of human beings to external events: emotion, thought, decision, action. The concept of sequel serves as the glue between scenes, as well as between paragraphs, along with the concepts of stimulus and response, and cause and effect, and much more stuffily, Swayne’s motivation-reaction units, or MRUs).

Internalization: based on the word think: direct one’s mind toward someone or something; use one’s mind actively to form connected ideas. In fiction, as opposed to a simple thought tag, internalization refers to those occasions in which the reader is drawn deep within a point-of-view character’s mind. Based on the concept of psychic distance, internalization results when the “camera” is turned inward and focuses really tight as the character reacts to something that has just happened. And while sequel and internalization are closely related, I think it’s instructive to consider them separately.

With those definitions in mind, let’s say you are a sit-down-and-write novelist with a completed first draft. If you begin the revision process by editing at the sentence level, larger issues will likely remain invisible. Holly Lisle’s “How to Revise Your Novel” course begins with two macro tasks: assessing the novel you wrote, then comparing it with the novel you intended to write. This “triage” identifies what needs to be changed during “major surgery” long before you begin “cosmetic surgery.”

My concept of “color-coded text time” is a far less detailed approach, and I offer it here in no way as a replacement for the utility of Lisle’s course. It’s simply another tool for taking a broader view of your novel. Nor is it absolutely pure, of course, in that some text can serve more than one purpose. But I contend that if you assign different highlight colors to these elements and apply them to any writing sample, you can at a glance visualize the writer’s intentional or unintentional choices with regard to the relative proportion of each.

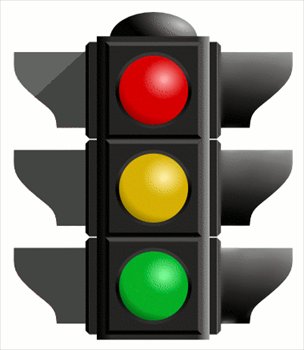

To borrow from my personal frustrations associated with driving in Austin traffic (in which I often want to help a motorist ahead understand traffic signals by politely saying, “Since green begins with a ‘g,’ you can easily associate it with ‘gas’ and ‘go'”), I might assign that color to all text that represents a real scene as defined above. The analogy fits well because scenes are the “go” juice that propel a story forward by advancing current story time.

To borrow from my personal frustrations associated with driving in Austin traffic (in which I often want to help a motorist ahead understand traffic signals by politely saying, “Since green begins with a ‘g,’ you can easily associate it with ‘gas’ and ‘go'”), I might assign that color to all text that represents a real scene as defined above. The analogy fits well because scenes are the “go” juice that propel a story forward by advancing current story time.

Backstory and background in particular represent the antithesis of scene. Every “rewind” into the past brings current story time to a screeching halt. They are essential elements of storytelling, but if not carefully handled, they rob fiction of movement in the wrong places and at the wrong times. There’s only one higfhlight color that fits, obviously. You see it far more than the other color in Austin traffic.

None of this is to imply that a large section of red-highlighted text is always a mistake. It’s the writer’s job to carefully consider the what, when, and why that put it there. On the other hand, the significant presence of red text early in a novel carries the risk of failing to engage readers well enough to hold their interest.

And yes, I appreciate the opinion of some that readers of mainstream literary fiction are generally more tolerant of slower pacing. But when you consider a multi-page writing sample with more red than green, I submit that scene selection and strategy are worth another look. And with additional colors assigned to the other structural elements, the proportional text time devoted to each can also be assessed.

In conclusion, green is good because your story is going somewhere.