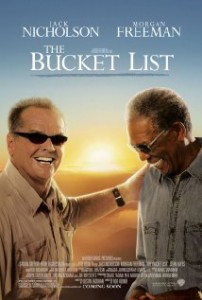

Until the movie came out, I’d never heard the term “bucket list.” Although I had lists of things I wanted to do, both conceptually and literally, thinking about them triggered the image of a stove. That’s probably because I’m a pretty good cook. But for whatever reason, the lists were labeled “Front Burner” and “Back Burner.” In retrospect, it seems strange that with my background as a fighter pilot I didn’t have an “After Burner” list. Maybe I’ll start that one today and see where it takes me. Or maybe not . . .

Until the movie came out, I’d never heard the term “bucket list.” Although I had lists of things I wanted to do, both conceptually and literally, thinking about them triggered the image of a stove. That’s probably because I’m a pretty good cook. But for whatever reason, the lists were labeled “Front Burner” and “Back Burner.” In retrospect, it seems strange that with my background as a fighter pilot I didn’t have an “After Burner” list. Maybe I’ll start that one today and see where it takes me. Or maybe not . . .

In my younger days, the lists frequently lengthened when I’d decide to educate myself about a subject, or learn to do something that looked interesting, or experience the enjoyment of a new hobby. It never occurred to me that anything on the list wouldn’t get done. The only limiting factor was under my control, the decision of when to transfer an  item from the back burner to the front and turn up the heat.

item from the back burner to the front and turn up the heat.

About ten years ago, the lists stabilized and then began to shrink. Not because I’d gotten any better at back-to-front burner transfers, but because the items required a younger body with fewer miles on it, or a commitment of time I wasn’t sure I had.

The motivation behind launching this topic probably flows from the very real possibility that one particular item on the list has drifted out of reach: the dream of building and flying my own airplane.

Any readers who have visited the Rants and Raves logbook and read “A Pilot’s Widow Has No Regrets” and “Do Home-Built Airplanes Come with Barf Bags?”  know of my interest in what the FAA calls “experimental” airplanes. Without trying to re-publish the information in those posts here, suffice it to say that the FAA’s designation is misleading, and the key difference between an airplane classified as experimental and any other is whether it was constructed by a manufacturer and offered for sale to the public, or by an individual for personal use.

know of my interest in what the FAA calls “experimental” airplanes. Without trying to re-publish the information in those posts here, suffice it to say that the FAA’s designation is misleading, and the key difference between an airplane classified as experimental and any other is whether it was constructed by a manufacturer and offered for sale to the public, or by an individual for personal use.

To the non-flyer, and some flyers as well, the idea of getting airborne in an airplane you built yourself is absolutely insane. I understand the sentiment, and at the same time have for years eagerly anticipated the moment when I might do exactly that.

It hasn’t always been that way. In February of 1994, I hadn’t flown anything smaller than a DC-9 since December of 1986. Airline flying bored me to tears. My wife and I had been talking about my checking out in a single-engine airplane so we could take some cross-countries to visit friends and family, and I suggested that we combine that objective with getting a tailwheel endorsement on my pilot’s license. You can visit the Single Ship logbook post “Taildraggers and Noserollers” for the difference between “tricycle” (or “conventional”) gear and tailwheel airplanes.

It hasn’t always been that way. In February of 1994, I hadn’t flown anything smaller than a DC-9 since December of 1986. Airline flying bored me to tears. My wife and I had been talking about my checking out in a single-engine airplane so we could take some cross-countries to visit friends and family, and I suggested that we combine that objective with getting a tailwheel endorsement on my pilot’s license. You can visit the Single Ship logbook post “Taildraggers and Noserollers” for the difference between “tricycle” (or “conventional”) gear and tailwheel airplanes.

At that time, only two local instructors provided tailwheel instruction. One was based at the Austin Executive Airpark with a Cessna 170, and the other at Kitty Hill (a private airport with grass runways), with a Piper Cub.

At that time, only two local instructors provided tailwheel instruction. One was based at the Austin Executive Airpark with a Cessna 170, and the other at Kitty Hill (a private airport with grass runways), with a Piper Cub.

I’d heard about Cubs for years  but never flown one. Eager to find out why so many pilots talked of them with such reverence, I contacted the instructor at Kitty Hill and was disappointed to learn that we wouldn’t be able to begin until later in the spring. I couldn’t wait, so I obtained my training at Austin Executive in the C-170.

but never flown one. Eager to find out why so many pilots talked of them with such reverence, I contacted the instructor at Kitty Hill and was disappointed to learn that we wouldn’t be able to begin until later in the spring. I couldn’t wait, so I obtained my training at Austin Executive in the C-170.

As soon as I could, on April 4, 1994, I drove to Kitty Hill for my first flight in a J-3 Cub. The instructor was finishing up with another student, so I walked over to an airplane parked under the trees. I had no idea what it was.

Tosh, meet an RV-4.

Ohmigosh. How cool is this?

As I stood there with my jaw figuratively (if not literally) hanging loose, my instructor’s partner in the flight school walked up. “You like it?”

“No. I’m just bored out of my skull waiting for the other guy.”

We laughed at that obvious fabrication, and I quickly learned that the owner/builder was in the market for a partner to purchase half ownership of the airplane. He was building another one, modified for a larger engine, and he needed some cash to continue with that project while still having access to an airplane. On May 19, 1994, I received the first instruction in my half of N252MD. This partnership gave me an up-close-and-personal look at the world of constructing and flying homebuilt aircraft, and the dream of one day doing that myself went on the back burner . . . where it still sits, almost seventeen years later.

My intention for this series of posts is to explore a dream that is so tantalyzing to me and utterly unfathomable to others. In spite of that, I hope you will join me for future “Bucket List” installments in the Single Ship Logbook.