Following my first solo flight in the T-37, I flew a combination of solo and dual sorties. Initially, solo flights were conducted within the traffic pattern, kind of like keeping the chicks close to home. Once cleared for solo flight to the practice areas, I felt a special kinship with a falcon in training whose jesses have been removed for the first time.

Following my first solo flight in the T-37, I flew a combination of solo and dual sorties. Initially, solo flights were conducted within the traffic pattern, kind of like keeping the chicks close to home. Once cleared for solo flight to the practice areas, I felt a special kinship with a falcon in training whose jesses have been removed for the first time.

No more instructor sitting in the right seat finding fault with everything I did, or stationed in the Runway Supervisory Unit watching my every move with binoculars so he could write derogatory comments about my traffic patterns in my grade book. Just me, my T-37, and the sky.

During one of my early solo rides un-tethered to the airport, I discovered smack-dab in the middle of my assigned practice area a sun-lit pillar of brilliant white cumulus clouds framed by a clear blue backdrop. Fair-weather cumulus, as it’s called, forms when heated, relatively moist air at the surface rises and cools, driving the moisture out of solution. The rising air creates a vacuum below, which draws in more air to accelerate the process. I was looking at an embryonic thunderstorm, and under certain conditions, it could develop into a real monster. But not yet, and probably not that day.

The column of cloud began below me and extended well above my current altitude of about 15,000 feet. Having recently transitioned from single-engine trainers that typically don’t fly much higher than 5,000 feet, this was my first opportunity to experience up close one of nature’s truly beautiful weather phenomena. Like a metal shaving to a magnet, it drew me closer.

The column of cloud began below me and extended well above my current altitude of about 15,000 feet. Having recently transitioned from single-engine trainers that typically don’t fly much higher than 5,000 feet, this was my first opportunity to experience up close one of nature’s truly beautiful weather phenomena. Like a metal shaving to a magnet, it drew me closer.

Circling near the lower portion of the pillar, I noted the rising motion of the clouds that gave testimony to the power building within, then glanced above me and wondered what it would look like at the top. I had sortie objectives to complete, but nothing I hadn’t performed well in the past, so resisting the temptation was out of the question.

But first, I’d need airspeed, so I turned away to get some room to accelerate. With the cloud a few miles at my six o’clock, I reversed course, pushed the throttles forward to the stop and unloaded the jet into a descent to trade altitude for speed. Approaching the base of the cloud at very near “red line,” or maximum allowable speed, I hauled back on the stick to point the nose straight up, rolled 90 degrees left, and looked over my shoulder at the cloud, so close I wanted to reach out and touch it.

I’m sitting there with a billowing white cloud just off the left wingtip and having a ball when it dawns on me that I’m slowing down too fast and may not make it to the top. As I run out of airspeed and the aircraft shudders with the approaching stall, the cloud top is still going strong, roiling skyward unabated. Claimed by gravity, I fell away with a new-found respect for Mother Nature.

I’d just completed my official sortie objectives when I reached “bingo” fuel, or the minimum amount for returning to base with an adequate safety margin. Now, where in the hell am I?

Much of West Texas is divided by section lines into squares, and the grid pattern on the ground provides convenient references for positioning the airplane to begin a maneuver and stay on the intended line until completion. That’s the good news. The bad news is that one section line looks like any other and a whole bunch of them together look the same no matter where you look. (Note: the picture to the right was taken in Kansas. For West Texas, think brown.)

Much of West Texas is divided by section lines into squares, and the grid pattern on the ground provides convenient references for positioning the airplane to begin a maneuver and stay on the intended line until completion. That’s the good news. The bad news is that one section line looks like any other and a whole bunch of them together look the same no matter where you look. (Note: the picture to the right was taken in Kansas. For West Texas, think brown.)

A quick scan of the terrain below found nothing familiar. But that was no sweat because I knew where the base had to be in relation to the practice areas, so I turned in that general direction and began looking for recognizable landmarks. When none appeared after a few minutes, I altered heading and flew for awhile, then saw a water tower we used as a reporting point. But as I got closer, the road pattern around the tower didn’t match what I remembered.

We were taught in private pilot training that water towers usually have the name of the nearest town stenciled on them, and to go take a look if we ever needed to confirm our position. Lot of good that would do me now. No way was I going to take that jet down into the weeds, which would probably generate a complaint from some farmer about being buzzed by one of them flyboys.

We were taught in private pilot training that water towers usually have the name of the nearest town stenciled on them, and to go take a look if we ever needed to confirm our position. Lot of good that would do me now. No way was I going to take that jet down into the weeds, which would probably generate a complaint from some farmer about being buzzed by one of them flyboys.

Even that early in my career, I knew that pilots never admit to being lost. We’re just “temporarily disoriented.” But after milling around the area watching my fuel state decrease, I realized that my confusion threatened to become permanent. It was time to come up with another plan.

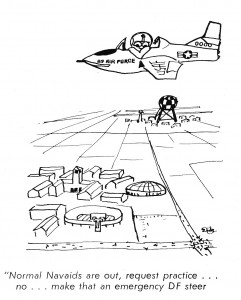

Early in training, we were taught about a system known as “direction finding” and how to use it in the event we ever became disoriented while in the practice areas. The demonstration with an IP aboard involved transmitting on a preset radio frequency so that “Reese Homer” could obtain a bearing on our radio signal and issue a heading to return to base. Instructors made the point loud and clear that if we were solo and ever had to use a “DF steer” for real, we were not to use the preset, practice frequency, but the standard “Guard” emergency channel automatically monitored by all control facilities and every USAF airplane.

Early in training, we were taught about a system known as “direction finding” and how to use it in the event we ever became disoriented while in the practice areas. The demonstration with an IP aboard involved transmitting on a preset radio frequency so that “Reese Homer” could obtain a bearing on our radio signal and issue a heading to return to base. Instructors made the point loud and clear that if we were solo and ever had to use a “DF steer” for real, we were not to use the preset, practice frequency, but the standard “Guard” emergency channel automatically monitored by all control facilities and every USAF airplane.

But that would announce to the world that I had temporarily lost my way. Why do that and take all that grief from my fellow students, not to mention being scolded by my IP? And maybe bust the ride and get a “pink” slip? So I used the preset frequency to avoid all that unpleasantness.

Meanwhile, a classmate of mine was participating in a required training session in which students spent time in the control tower. In this case, he was sitting beside the radio console with the DF steer equipment. When I called Reese Homer for a practice DF steer, the operator initially assumed I was doing so for training. But when he got the first bearing to my position, he realized that I wasn’t within the boundaries of the practice area. He immediately switched to Guard channel, so his transmissions to me were overheard by every Reese pilot airborne at the time. So much for maintaining a low profile, and it got even worse.

After Reese Homer issued a few heading corrections to point me directly at the airfield, he asked me if I had the field in sight. I didn’t, so he repeated the question at intervals, until in total exasperation, he told me something to the effect of, “Roll upside down and look out the top of the canopy.” He’d brought me directly over the field and I’d never seen it.

After Reese Homer issued a few heading corrections to point me directly at the airfield, he asked me if I had the field in sight. I didn’t, so he repeated the question at intervals, until in total exasperation, he told me something to the effect of, “Roll upside down and look out the top of the canopy.” He’d brought me directly over the field and I’d never seen it.

That little fiasco earned me a pink slip for the ride, unrelenting grief from my classmates, and the nickname, “Dee Eff.” It was one of my first encounters with the potential humiliation that hid in ambush just around the corner throughout my career in military aviation. Everything was graded in one way or another. Need some slack? Forget about it.

Strangely enough, I miss it still.