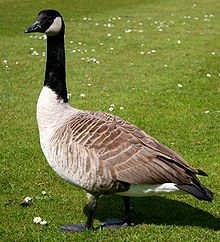

As far as we know, neither of the Wright brothers ever collided with a bird in their Flyer, and I doubt they even considered the possibility. But 107 years later, every pilot is aware of the danger. And since January 2009, every non-pilot is as well due to the high-profile “Miracle on the Hudson” collision between an airliner and a flock of Canadian geese.

As far as we know, neither of the Wright brothers ever collided with a bird in their Flyer, and I doubt they even considered the possibility. But 107 years later, every pilot is aware of the danger. And since January 2009, every non-pilot is as well due to the high-profile “Miracle on the Hudson” collision between an airliner and a flock of Canadian geese.

This morning’s Statesman has an article about a government biologist tasked with keeping airports free of birds. The Humane Society of the United States calls him a “contract killer.” If you read the article, you might agree because he uses lethal methods for reducing bird populations in the vicinity of airports.

The question then becomes if more humane options exist to address the problem. Animal rights activists have suggested using border collies to chase away Canadian geese, for example, but that doesn’t send them far enough away for good. Birth control doses in bird food attract more flocks in the sort term. Other “in-the-nest” tactics have proven ineffective as well. No matter what side of the issue you’re on, the reality is that the problem will not go away, and it can’t be ignored.

According to FAA records, since 1990 bird-strike counts have risen dramatically (from almost 2000 to over 7000 per year) due to rising air traffic, growing avian populations, and more thorough reporting. The probability of a mid-air collision between a bird and an airplane is clearly illustrated by the following statistic: since 1970, the population of Canadian Geese in the US rose from 230,000 to almost 4 million. Without enough predators to keep them in check, the problem will only get worse.

My initial awareness of the potential danger came in Undergraduate Pilot Training. During initial academic instruction on the T-37, we had to memorize almost anything that had numbers in it. One flight manual description, for example, referred to the bird-strike resistance of the windscreen. I don’t remember the exact wording, but the manual noted something to the effect that the windscreen was designed to withstand the impact force of a 4-ounce bird at 270 knots. Even without the likely inaccuracy of my memory, it sounds silly to suggest that any component of a 6500-pound airplane can be vulnerable to such a lightweight object.

My initial awareness of the potential danger came in Undergraduate Pilot Training. During initial academic instruction on the T-37, we had to memorize almost anything that had numbers in it. One flight manual description, for example, referred to the bird-strike resistance of the windscreen. I don’t remember the exact wording, but the manual noted something to the effect that the windscreen was designed to withstand the impact force of a 4-ounce bird at 270 knots. Even without the likely inaccuracy of my memory, it sounds silly to suggest that any component of a 6500-pound airplane can be vulnerable to such a lightweight object.

But physics rules the world, and the operative concept here is: inertia equals mass times velocity squared. The bottom line is that the effect of the velocity at impact increases the forces exponentially. Relatively light objects going fast can do lots of damage. And although one of my fellow students got the concept backwards, he created a rare moment of levity during a question-and-answer session with one of our flight instructors.

A typical start to the flying part of our day began sitting around a table with four students and an instructor, who would open up a flight manual and randomly choose an aircraft system, or limitations, or procedures as the source for trying to make one of more of us look like fools. At least that’s what we students thought. In this case, the instructor asked the class clown to describe the impact resistance of the T-37 windscreen.

“Sir! The windscreen in the T-37 Tweety Bird is capable of withstanding impact with a 270-ounce bird at 4 knots, Sir!”

That display of minor insubordination earned him a “pink slip,” but he told us later that the look on the instructor’s face made it worthwhile. But all joking aside, it’s a serious matter.

A T-37 instructor pilot was decapitated when a sand hill crane came through his windshield at 320 knots. The other pilot, also an instructor, flew the headless body home. A solo student in a T-38 hit a flock of cranes and lost one engine and his windshield, but not his head. He landed the plane, barely able to see through the bird blood on his helmet visor.

A T-37 instructor pilot was decapitated when a sand hill crane came through his windshield at 320 knots. The other pilot, also an instructor, flew the headless body home. A solo student in a T-38 hit a flock of cranes and lost one engine and his windshield, but not his head. He landed the plane, barely able to see through the bird blood on his helmet visor.

In almost fifty years of flying, I’ve experienced only two bird strikes. The first occurred in an F-4E at 450 knots about 200 feet above the Nevada Desert. I happened to look to my right as a black object came into view, far too late to take evasive action. Instinctively, I turned my head to the left and down. To this day I can clearly remember the sound. During the debriefing, I described it as if I had been sitting on the ground in the cockpit and someone hit the windscreen as hard as they could with a bat.

To counter the dubious looks that comment received, I pulled out my personal cassette recorder. In those days, we didn’t have onboard voice-recording systems, and it was common to tape the missions for use in debriefing. And there in the midst of all the other sounds filling a fighter cockpit at 450 knots, the THWOCK! of that bird hitting my windscreen could be clearly heard, followed immediately by an expletive from yours truly.

My second bird strike occurred in a CitationJet during takeoff from Southeast Texas Regional Airport at Beaumont. The automated terminal information service there includes a never-ending caution about birds in the vicinity, as well it should considering proximity to the Gulf of Mexico and heavy concentrations of waterfowl.

Any pilot knows that birds don’t have training in instrument flight. With the clouds hugging the surface that day, how many millions of seagulls were grounded? As I took the active runway, forward visibility might have been a half-mile or so, but the absence of contrast in the grey mist made for a homogenous view of the world in front of the jet. What happened next still plays like a video on my memory screen.

Any pilot knows that birds don’t have training in instrument flight. With the clouds hugging the surface that day, how many millions of seagulls were grounded? As I took the active runway, forward visibility might have been a half-mile or so, but the absence of contrast in the grey mist made for a homogenous view of the world in front of the jet. What happened next still plays like a video on my memory screen.

Approaching two critical points in the takeoff roll referred to as “V-one,” and “Rotate,” at which time standard procedures call for taking my right hand off the throttles and pulling back on the control yoke with both hands, I noticed something that just didn’t seem right.

The concrete on the runway seemed to be moving, like pieces of it were beginning to rise. The nose was coming up to takeoff attitude by this time, so it blocked my view of the runway and I still didn’t know what was happening until the windscreen filled with a flock of seagulls. Lots of seagulls. The one I locked eyes with as it took evasive action and whizzed by the side window at about 100 knots made it, as did all of the others except one.

This impact had a much more hollow sound than my previous encounter. Later I was able to attribute this to a combination of much lower velocity at impact and the fact that the seagull hit the fiberglass radome covering the weather radar. My reaction was the same: climb immediately for altitude and check the engine instruments. With no indication of engine damage and no way to confirm where the impact occurred on the airframe, I continued the short flight home to Austin. I did notice that the weather radar no longer worked normally. The antenna seemed to have stopped sweeping. After landing I discovered why. The radome had been punched in as if Paul Bunyon had hit it with a sledgehammer, and the antenna had jammed against it.

This impact had a much more hollow sound than my previous encounter. Later I was able to attribute this to a combination of much lower velocity at impact and the fact that the seagull hit the fiberglass radome covering the weather radar. My reaction was the same: climb immediately for altitude and check the engine instruments. With no indication of engine damage and no way to confirm where the impact occurred on the airframe, I continued the short flight home to Austin. I did notice that the weather radar no longer worked normally. The antenna seemed to have stopped sweeping. After landing I discovered why. The radome had been punched in as if Paul Bunyon had hit it with a sledgehammer, and the antenna had jammed against it.

The seagulls had gathered for a confab at the X intersection of two runways. I have no idea why. But I do know this: birds and airplanes don’t play well together.