If the title of this post is black, click on it to view the featured-image header and continue reading.

During my recent presentation “Pilot Error in Fact and Fiction” as a part of the UT LAMP Lecture and Seminar Series, discussing the role of human performance in aircraft accidents included an example of a how a mistake by an aviation mechanic could be the primary cause.

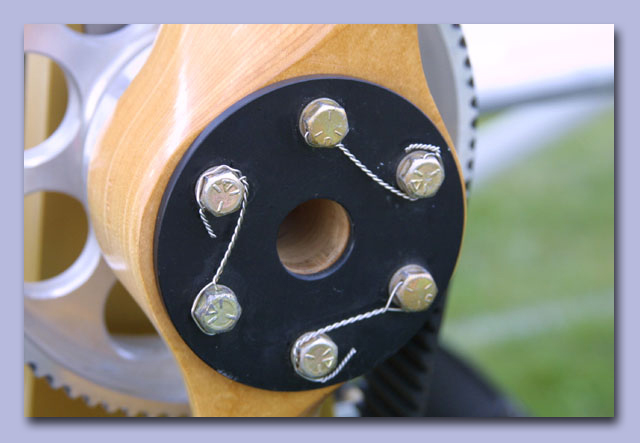

Any bolt in an airplane needs to stay put, and there are three methods used to ensure they do not loosen up. Bolts tightened to a specific torque value use safety wire to apply clockwise tension as shown in this image of six propeller attachment bolts.

Image credit ultralightnews.ca

Image credit ultralightnews.ca

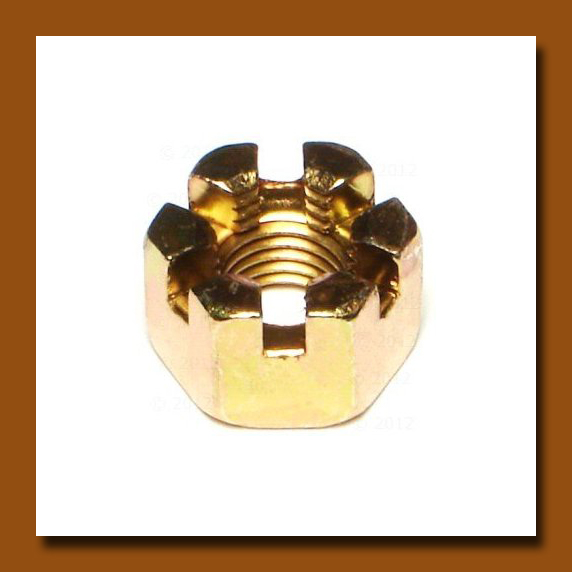

A castle nut is used in applications where a specific torque value is not critical and the primary objective is to prevent the nut from backing off. The nut is snugged down on the bolt and tightened until the nearest slot is lined up with a hole in the bolt. A cotter pin slipped into the slot, through the hole in the bolt, out the opposite slot in the nut and bent back onto itself secures the nut in place.

A nylon lock nut is remains in place because of the friction between the nylon insert and the threads on the bolt, which cut into the nylon as the nut is tightened. The are designed for one-time use.

If a bolt comes loose because it was not properly safety wired, for example, and that is determined to be the first link in the chain of events, the primary cause of the accident can be attributed a mistake by a mechanic. Such was the case as reported on AVweb:

NTSB Cites Maintenance Errors In Fatal Crash

A tourist helicopter that crashed in Nevada in December 2011, killing the pilot and two couples on a sightseeing tour over Hoover Dam, was brought down by an improperly fastened nut, the NTSB determined on Tuesday. The investigators found that a maintenance crew working on the Eurocopter AS350-B2 before the flight had probably reused a self-locking nut that should not have been reused. The nut failed in flight, making the aircraft uncontrollable. The mechanic and a supervisor both had been called in to work on their day off, the board said, and fatigue was cited as a factor. NTSB Chairman Deborah Hersman said the accident shows that mechanics need to use checklists in their work, just as pilots do.

A tourist helicopter that crashed in Nevada in December 2011, killing the pilot and two couples on a sightseeing tour over Hoover Dam, was brought down by an improperly fastened nut, the NTSB determined on Tuesday. The investigators found that a maintenance crew working on the Eurocopter AS350-B2 before the flight had probably reused a self-locking nut that should not have been reused. The nut failed in flight, making the aircraft uncontrollable. The mechanic and a supervisor both had been called in to work on their day off, the board said, and fatigue was cited as a factor. NTSB Chairman Deborah Hersman said the accident shows that mechanics need to use checklists in their work, just as pilots do.

Finding the cause of the crash required “old-fashioned investigative gumshoe work,” Hersman said at the board meeting. The aircraft, operated by Sundance Helicopters, had no flight data recorder on board, there were no witnesses to the crash, weather was clear and calm, and there were not even any ATC tapes. Radar showed that the helicopter deviated from the usual tour route about one minute before the accident, first climbing and turning, then descending and turning again before impact. The helicopter was heavily damaged by the impact and a post-crash fire. A synopsis of the safety board’s findings is posted online; the full final report will be posted in several weeks.

Another example of human error from my presentation is fuel starvation. I used it to indicate how failure of a commercial airline operations dispatcher to consider the potential for rapidly changing weather to cause inflight delays might result in an aircraft not having adequate fuel reserves. In the example below from Avweb, however, the blame falls squarely on the pilot-in-command.

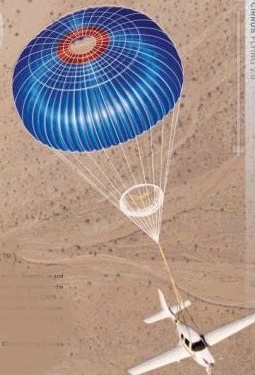

Danbury Chute-Pull Aircraft Out Of Fuel

The NTSB says a Cirrus SR20 that parachuted to safety last week in Danbury, Conn., was out of fuel. In its preliminary report on the incident, which was widely publicized in the mainstream media, the NTSB says the aircraft, with a flight instructor, another pilot and a third person on board, was on final for the Danbury Airport when the pilot flying radioed to air traffic control that the aircraft was “out of fuel.” Investigators later were able to drain just 26 ounces of fuel from the tanks and none had spilled when the plane settled to the ground about three miles from the airport.

The NTSB says a Cirrus SR20 that parachuted to safety last week in Danbury, Conn., was out of fuel. In its preliminary report on the incident, which was widely publicized in the mainstream media, the NTSB says the aircraft, with a flight instructor, another pilot and a third person on board, was on final for the Danbury Airport when the pilot flying radioed to air traffic control that the aircraft was “out of fuel.” Investigators later were able to drain just 26 ounces of fuel from the tanks and none had spilled when the plane settled to the ground about three miles from the airport.

The report says the flight originated in Danbury and the trio flew to Groton and landed. They were returning to Danbury when the prop stopped. The round trip was about 150  miles if both legs were flown direct. After making the radio call, the pilot pulled the parachute handle and the aircraft settled in some trees in a residential area, breaking off the empennage. There were no injuries. There was a remote data module on board and a memory card in the avionics and both have been sent to the NTSB’s lab for analysis.

miles if both legs were flown direct. After making the radio call, the pilot pulled the parachute handle and the aircraft settled in some trees in a residential area, breaking off the empennage. There were no injuries. There was a remote data module on board and a memory card in the avionics and both have been sent to the NTSB’s lab for analysis.

Note: The parachute visible in the photo above is not a personal chute. It was installed as part of the equipment aboard this Cirrus aircraft, and it’s designed to lower the entire aircraft safely to the ground as shown on the right. Safely, however, does not necessarily mean gently, and some aircraft damage can be expected. As mentioned in the article, the airplane landed in some trees, and the tail section broke off. Had it landed on flat terrain with no trees, that probably would not have occurred.

In any case, “There were no injuries” is the operative objective of this feature.